Plaudits have been exchanged recently for meeting the target of 33% female non-executive directors in the FTSE 350 under the Hampton-Alexander Review. Yet the same review shows this target has been missed in executive leadership. It points to a low appointment rate of women to senior leadership roles, too few female chief executives and finance directors, and several all-male executive teams persisting.

Why has the progress made in the non-executive space been even slower in executive teams, especially given the faster turnover of roles?

Our understanding of the barriers holding back talented women from the top jobs has progressed. Expansion in flexible working, paternity and shared parental leave and reductions in sexual harassment are mechanisms which reduce some of the structural barriers that hold women back. No longer innovative, these are standard practice for modern organisations. As a NED, you should know where your organisation stands on these policies.

However, we are yet to see much by way of results. Some argue that these things take time, and we must wait for the initiatives to filter through. If there’s one thing our experience in the non-executive space has proved, it’s patiently waiting for change is highly ineffective as a strategy.

We must also remember progress is not linear. There is now at real risk of a roll back in gender equality, with the IFS reporting mothers being 1.5 times more likely as fathers to have lost or quit their jobs since the start of the pandemic.

Creating an organisation where women reach the most senior levels, in proportionate numbers, needs to be considered as a major change programme.

After all, overwhelmingly male leadership teams and the gender pay gap are “business as usual”. However, around three-quarters of major change programmes fail, with “misdiagnosis” or poor strategy being the root cause (as reported by the HBR).

This is where board-level leadership is crucial. All boards should be asking themselves what results they want to see on diversity, how big a shift this is from “business as usual” and allocating the corresponding resources.

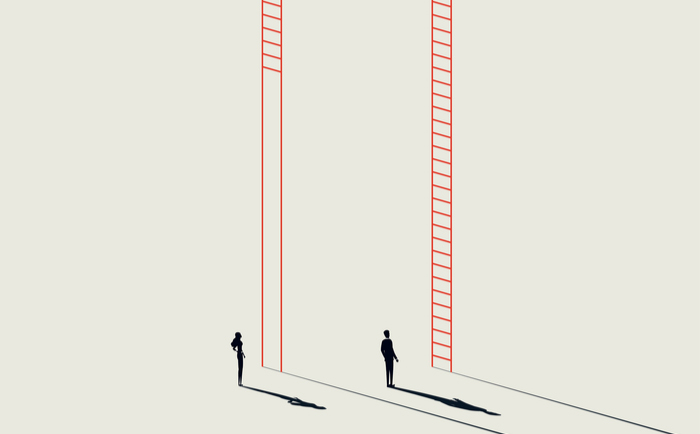

Understanding your data is key. Where does your gender balance begin to break down? For some industries, there is an entry-level issue with fewer young women choosing STEM careers, for example. For others, McKinsey’s Women in the Workplace report identifies, not the famous glass ceiling, but a “broken rung” where a gender promotion gap begins at the first step up to manager.

Your gender pay gap data is also vital. Rather than box tick for government, it shows you where in your organisation women are valued differently to their male counterparts. I recommend the board seeing not just the overall pay gap, but understanding the picture by division, region or department.

Women and the “traditional” leadership mould

Good analysis of this data will give you a picture of where the problems lie. But then what?

Most organisations have realised even the most progressive policies can only ever be part of the solution. They know that culture is key to creating inclusion which allows all to thrive and feel confident to use the policies in place.

Unfortunately, many of the approaches taken to addressing organisational cultures can be likened to a chocolate teapot—momentarily tasty at best, or more often, down-right frustrating.

McKinsey estimates that US companies alone have spent $8bn on unconscious bias training. Yet the outcomes of this type of training are proven to be negligible, if not actively counter-productive.

We also have seen many initiatives which attempt to “fix the women” to succeed within the male-centric norms. At worst, I have come across personal branding workshops more suitable to accruing social media followers than becoming an effective business leader. I see little need for research to evaluate their impact, as women have largely voted with their feet away from these patronising initiatives.

Mentoring with senior leaders appears more promising. However, without training in mentorship, leaders can only share what worked for them personally in the past. We do not need to encourage today’s top female talent to become more like those who succeeded in a different mould.

I am not arguing against investing in your female talent.

What is needed today is wise investment. Women are less likely to enjoy a “natural” career progression, as they do not “look like” the traditional leaders. Everyone today has biases, conscious and unconscious, thus it is crucial that you recognise yours (and your bosses’) and work out a career strategy to either consciously include or manage your way around them. Like it or not, active career management is vital.

At Women on Boards, our career development work with our corporate partners starts from the premise that talented professionals can form their own career plans. They simply need research-based information about what works and what to prioritise. Applying it to their own careers is something those who are truly high potential can do all by themselves.

Similarly, Women on Boards’ leadership programme does not attempt to mould women’s leadership style. Although its primary focus is on cutting-edge leadership techniques, it recognises that women—or others who do not “look like” traditional leaders—need to provide extra reassurance to interviewers that they are both confident and competent to step up. Rather than a change of style, this requires learning the language of leadership and how to articulate specific examples for what are often fairly intangible competencies, such as “being strategic”.

It is support and investment in this mould which I believe will really deliver results, both for women and other under-represented groups.

A truly inclusive culture

Perhaps counterintuitively, I am going to argue for investing in your male leaders as well.

What’s needed is a truly inclusive culture, one which all leaders—male and female—need to create. Investment is required to equip all senior leaders with the proven techniques to operate inclusively and focus on performance, not “fit” with an established (white, male) team.

This is no mean feat. It is far more difficult to manage a diverse team. It requires adaptive styles of leadership and ability to balance and facilitate divergent opinions. Diversity correlates with better business performance, but it needs the right leadership style to enable those benefits to flourish. This is what our “Getting to the C-Suite” leadership programme teaches at senior level. However, investment is needed at every tier of management—remember, McKinsey’s “missing rung” on the ladder.

My plea to boards considering diversity and inclusion initiatives is to ask one simple question: “Does it work?”

That’s to say, to have a clear outcome in mind, ideally supported by measurable KPIs. And then to probe the evidence that the proposed intervention will, or is at least likely to, create the desired result.

Like the best simple questions, answering this is tough. Evidencing cause and effect of a single initiative on broad cultural change is unlikely. However, more specific results should be evidenced.

To use our own example, I make no apologies that our leadership programme aims to get women into more influential roles. Now we have a sizeable cohort of alumnae, I looked at the data. Over its first five years, 70% of our alumnae have gone on to a challenging new role and/or gain non-executive positions. A further 7% were already in C-Suite or NED roles, and had joined the course for skills development alone. I can say categorically that it works.

Please demand a similar level of evidence that your diversity and inclusion investments will be well-spent. Women don’t need “fluff” training, they want leadership tools around strategic thinking and effective leadership approaches that drive competitive change.

Fiona Hathorn is CEO of career network Women on Boards.