As protests continue against the brutal killing of George Floyd by police in Minneapolis, corporate America has felt unable to remain quiet.

A slew of companies have made their views heard through press statements, tweets, TV ads, letters to customers and interviews, condemning racism and declaring the need for change.

The messaging has underlined the increasing trend for companies to become involved in social and political issues. For many others it will prompt difficult internal conversations about how they should demonstrate their commitment to core values, the messaging they should adopt and what it means to take a stand on such critical topics.

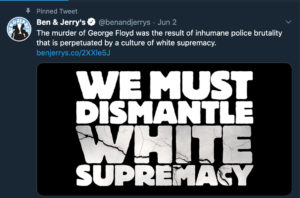

As more companies publicise their views, others will come under pressure to do likewise. Ice-cream maker Ben & Jerry’s tweeted: “The murder of George Floyd was the result of inhumane police brutality that is perpetuated by a culture of white supremacy.”

Nike, the sports brand, released an ad declaring: “Don’t pretend there’s not a problem in America,” and used the hashtag #UntilWeAllWin. Merck, the pharmaceutical giant, tweeted a message from chair and chief executive, Ken Frazier, following a TV interview, saying: “What the African American community sees in that videotape is that this African American man, who could be me or any other African American man, is being treated as less than human.”

Nike, the sports brand, released an ad declaring: “Don’t pretend there’s not a problem in America,” and used the hashtag #UntilWeAllWin. Merck, the pharmaceutical giant, tweeted a message from chair and chief executive, Ken Frazier, following a TV interview, saying: “What the African American community sees in that videotape is that this African American man, who could be me or any other African American man, is being treated as less than human.”

Chip Bergh, president and chief executive of fashion brand Levi Strauss, issued a statement condemning racism and added the protests were also about inequalities in the US revealed by the Covid-19 pandemic, and about history. “It’s about a shameful and destructive lack of progress on race and equality in a country that celebrates progress in so many other areas,” he said.

While many of these statements seem easy to publish, business pages have carried statements from campaign groups revealing they have been inundated with enquiries from corporates seeking advice on how to best deal with their reaction to the protests.

While many of these statements seem easy to publish, business pages have carried statements from campaign groups revealing they have been inundated with enquiries from corporates seeking advice on how to best deal with their reaction to the protests.

That may be because—as a Washington Post article puts it—“silence is not an option” on this issue; any attempt to remain “neutral”, or duck the subject, is “contributing to the problem of racism”.

But there is an additional question for companies: it’s one thing to make statements, it’s another to live by the values you talk about. Already there are warnings that many companies rushing to have their views heard could find themselves under close scrutiny.

‘Political corporate social responsibility’

This could be through the composition of their boards. In the UK, for example, the Parker Review found only 53 of the FTSE 100 could claim to have at least one board member from an ethnic minority. Launched in 2017, the Review gave companies until 2021 to resolve ethnic minority representation on their boards. Progress is slow.

The lesson here is that observers will look for public statements of support to be accompanied by policy making. One London-based inclusion adviser warned: “It’s difficult to spot who is doing this genuinely and who is jumping on the bandwagon.”

—London-based inclusion adviser

And that is important because in the absence of guidance from political leaders the public increasingly looks to corporate chiefs to steer them through difficult times. The 2020 Edelman Trust Barometer found that while only 42% of people trust politicians, 51% trust chief executives. Among employees, 92% believe their CEOs should speak out on important issues.

Indeed, that is exactly what many companies have been doing. The growth of corporate responsibility as a guiding concept, as well as a clearer understanding of the financial benefits of being in tune with public sentiment on political questions, has prompted many managers and boards to tailor both their business strategies and marketing.

But even if it is a marketing ploy, many commentators note it may still be significant. Australian academic Bree Hurst agrees and argues there is a need for “political corporate social responsibility” from companies because it responds to consumer demands and fills “regulatory gaps” left by governments.

“Among the gaps in the US system contributing to overpolicing of black communities is the failure to provide equal access to public goods like education, health care and even clean air,” she writes.

Substantive policies

Statements of support, or “solidarity”, have their uses, according to Doyin Atewologun, an academic adviser to the Parker Review. She describes them as a “very powerful influencing technique” that can have an effect, especially over competitors who may be compelled to respond in kind. But, she adds, they should not be delivered in isolation. They must be accompanied by substantive policies too.

—Doyin Atewologun, adviser to the Parker Review

“One of the challenges I have with the statements out there,” says Atewologun, “is that they are broad brush; they don’t commit the organisations to anything in particular. They are statements of solidarity that do not hold anyone accountable, generally speaking, and don’t actually show the role that they [corporates] play in disrupting the structural racism that everyone is talking about.”

Messages should therefore centre on the roles companies “perceive they play in society”, for example the way Nike relates to disadvantaged and marginalised groups.

There are two other risks associated with messaging during an event like the current protests, says Atewologun. One is that corporates associate action, or messaging, with “flashpoints” instead of confronting an issue in depth and over the long term. Or, as in the current case, accepting that “people of colour are grappling with this every single day and it’s not one big incident”.

The other risk, she says, is taking advice from the “loudest” high-profile voice instead of seeking out advisers with a “track record” offering guidance “drawing on research and an evidence base”.

In the coming weeks and months company leaders and boards will continue to confront the issue of rascism. Corporate responsibility is an increasingly important factor and more boards will need to accept it becoming central to the way they operate in society. Many consumers expect them to take a position. But those that do so without their own underlying policy changes may well be exposed by close scrutiny.