Julia Hoggett, CEO of the London Stock Exchange, wants us to have a constructive discussion about the UK’s approach to executive compensation. More specifically, she believes that investors should back higher CEO pay to discourage companies from moving their stock market listings overseas. Her boss, David Schwimmer, CEO of the London Stock Exchange’s parent company, agrees, arguing that UK companies need to pay more to compete with US businesses. (He would be a beneficiary of such an approach).

The counter argument is that this is what Martin Wolf, the FT’s chief economics commentator, calls “magical thinking“. It is like Liz Truss’s policy of slashing the top rate of income tax in order to tackle the UK’s economic growth problem.

The UK economy’s competitive position is more likely to be a consequence of political upheaval, unpredictable international trade policy, a dearth of available capital in the UK, and the lack of a coherent industrial policy, rather than failure to pay top executives at rates commensurate with those paid in the US.

So who’s right?

The main economic theory of executive compensation, known as “optimal contracting”, postulates that big companies are more complex, and therefore more difficult to run, than smaller companies. The largest companies must attract the best management talent in order to run efficiently. They should therefore provide the biggest pay packets.

Optimal contracting theorists also argue that the actions of CEOs have a multiplicative effect on growth in firm value, because their actions are scalable. A CEO whose strategic decisions double the size of a $2bn company creates much more shareholder value than a CEO whose actions double the size of a $1bn company.

In a much cited academic paper, two well-known economists, Xavier Gabaix and Augustin Landier, provide evidence in support of the relationship between company size and CEO pay. Their research looked at US CEO pay data for the period 1992-2004. A subsequent paper covering the years 2004-2011 (including the global financial crisis) provides additional support for the theory.

What about the UK?

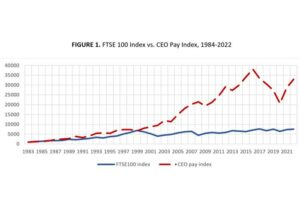

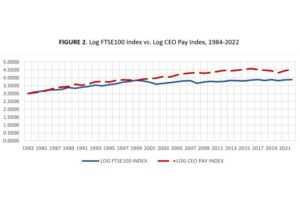

The two charts shown below illustrate the UK’s position. Figure 1 plots the growth in pay of UK FTSE 100 CEOs since 1984, when the FTSE 100 index was launched. Figure 2 charts the logarithm of the FTSE 100 index with the log of an index of CEO pay starting in the same year. (Logs of the two indices are used to deal with the multiplier effect of growth in firm size assumed by optimal contracting theory).

The close match of the lines in Figure 2 suggests that Gabaix and Landier’s thesis is also consistent with UK pay data. In other words, there is no evidence that UK CEOs are underpaid compared with their US peers, especially when the size of the companies they run is taken into account.

FIGURE 1. FTSE 100 Index vs. CEO Pay Index, 1984-2022 (Source: this author)

If you think about it, at first sight, this all makes perfect sense. The size of the US economy (around $25tn) is eight times the size of the UK economy (around $3tn), and the population of the US (330m) is nearly five times the size of the UK (68m). It is hardly surprising that US companies are much bigger than UK companies.

Of the world’s 100 largest companies by market capitalisation in 2022, 57 were based in the United States; 11 were based in China. Only five of the global top 100 companies, AstraZeneca, HSBC, Linde, Shell, and Unilever, had their primary listings on the London Stock Exchange.

In 2022, the average pay of S&P 500 CEOs was $25.2m (£20.4m). Median pay of FTSE 100 CEOs was £3.9m ($4.8m). According to optimal contracting theory, this is entirely predictable.

“But”, the proponents of higher pay might argue, “this data is ‘after the fact’. If UK companies hired more talented CEOs by paying them more, perhaps a greater number of UK companies would grow to be as big and successful as US companies.”

Perhaps. But this really does look like magical thinking. It confuses cause and effect. The lion’s share of US CEO pay (around 80%) is provided in the form of equity-based compensation. The incentive effect of equity-based pay is the result of aligning the possibility of significant growth in compensation with the prospect of future growth in firm value. High equity-based pay should be an outcome, not an input.

My conclusion? The case for higher CEO pay is not proven. Those arguing for it will have to work much harder if they want to justify their claims. They need to start by answering the following questions:

- How many top executives have actually been lost to the US?

- Which companies have chosen to list in the US, rather than the UK, because of executive pay?

- Is US CEO pay the right benchmark—what about Europe, where CEO pay tends to be lower?

- Is the pull of private equity actually a greater problem? If so, what should be done about that?

- Are current compensation structures the right way of paying people anyway—would restricted stock be a better model, one that is potentially more motivational and probably less expensive?

- What would be the knock-on implications of higher pay for top executives—would it lead to higher wage demands from other employees?

- Should the boards of listed companies be concerned about the societal implications of rising inequality, or is this solely the responsibility of the government?

- And finally: what are the real reasons for the London stock market’s loss of competitive advantage?