It can cause bankruptcy and feel like a “violation”: Ransomware attacks are on the rise, enabling cybercriminals around the globe to extort vast sums of money from businesses while indiscriminately threatening their very existence.

The danger was recently thrown into sharp relief when reports emerged that the Brussels-based police forensic services provider Eurofins Scientific had paid a “huge ransom” of “hundreds of thousands of pounds,” to regain access to computer systems after criminals gained access to their networks. And this was after the involvement of intelligence agencies.

Ransomware also hit the headlines recently when music giants Radiohead were targeted. Criminals gained access to unpublished music archives and threatened to make them public unless the band paid up. Never ones to be intimidated, the band countered by simply making the tracks public themselves, thus removing the extortionist’s leverage.

On that occasion the extortionists miscalculated. Most victims, however, will not have the same advantage and a ransomware event becomes a nerve shredding process for managers as they weigh costs against potential disaster.

Managers at Eurofins could be forgiven for feeling outraged. Those who have seen the effects of ransomware attacks first hand have witnessed the damage it can do to companies and the individuals involved.

—Mark Deem, Cooley

According to Mark Deem, a partner and IT specialist with law firm Cooley, the distress is real. “You talk to some people who have had their house unfortunately broken into and you see that similar reaction in many ways in corporate executives… that they somehow have their company, their possessions, violated by a third party.”

The precise ransom payment by Eurofins remains unconfirmed, but the scale cited in reports would not be surprising. Local government organisations in the US have made public ransoms of up to half a million dollars.

These developments come as the number of ransomware attacks is expanding while, anecdotally, experts say the size of ransom demands is rising. While the targets used to be small and medium-sized companies, large corporations are beginning to find themselves in the cybercriminals’ crosshairs. That makes coming to terms with the possibility of an attack acutely important for IT departments and boards—non-executive and executives alike—concerned with the risk profile of their companies, their reputations and the survival of their businesses.

The most frequently publicised advice is straightforward: back up computer systems and ensure the backups are protected from cyber-intrusion and infection from ransomware. The less well illuminated area is what happens after an attack has begun. Moreover, how does a board reach the conclusion that a ransom payment is the only way forward, and what are the risks involved with that decision?

Growth industry

Ransomware is being taken seriously not only because of the risks to business, which are potentially lethal, but also because of the increasing scale of the problem.

The global cost of ransomware attacks has been estimated to be $20bn by 2021 in ransom payments and lost business, making it the fastest growing form of cybercrime. Databarracks, a firm of IT disaster recovery experts, estimates 28% of companies will be hit by an attack in 2019, up from 16% three years ago.

When Verizon Enterprise Solutions published its 2019 annual security report examining 41,000 IT security incidents, it found that 70% were aimed at financial gain and ransomware was the second most frequent “malware action” by criminals, behind “command and control” attacks sometimes to steal data. Verizon’s report says security specialists have “not learned” their lesson about ransomware and it remains “a major issue for organisations”. Things may be growing worse.

What is ransomware?

Ransomware is software (malware) used by criminals to either lock up or encrypt data owned by a target organisation. Ransomware doesn’t need to actually steal data to be successful as a method of extortion—it merely has to make it inaccessible or useless.

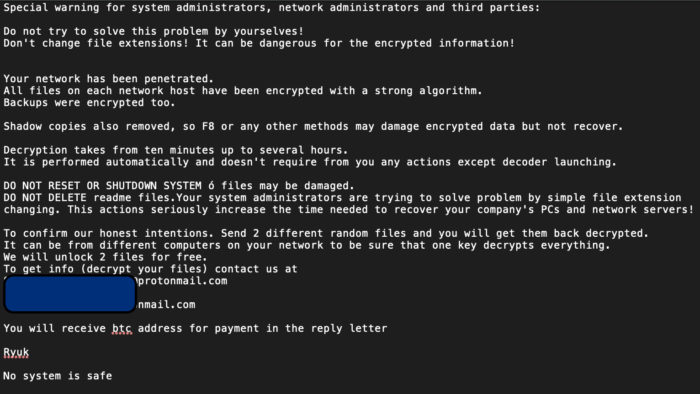

The first unexpected sign of peril often comes when workers log on in the morning to find a pop-up window on their screens (see photo) suggesting that data has been encrypted or locked away, that doing anything about it might damage or destroy the data and the only course of action remaining is to pay the cybercriminals large sums, usually in Bitcoin, to receive the decryption key.

Mark Deem describes ransomware attacks as typically coming in three levels of severity: First, entry level attacks consisting of nothing more than a pop-up window attempting to trick computer users into making payments. The cyber-intrusion goes little further than placing the window on screens with no real damage to the integrity of data.

The next level sees criminals “lock up” data making it impossible to access. “Like someone putting their padlock on your gym locker,” says Deem. The data is in situ and likely undamaged.

The most serious level is what has become known as the “cryptolocker” style of attack. Not only is the data locked up but it is also encrypted so it is no longer usable by the company and its employees.

—Peter Groucutt, Databarracks

It is a chilling moment. The criminals can’t be traced, their identities remain a mystery and the threat to the company can be existential. In addition, ransomware can bring with it a sense of helplessness because the criminals will frequently use customised malware unused anywhere else before. It is, unfortunately, open to very few remedies. According to Peter Groucutt, managing director of IT security firm Databarracks: “There are only two ways to recover from ransomware attacks—to restore the data from backups or to pay the ransom.

“You might get lucky and find that a decryption tool [key] has been created for your particular type of ransomware, but don’t count on it.”

Bill Siegel, chief executive and founder of New York-based security specialists Coveware, agrees: “By and large it’s not an option to crack the code.”

This inevitably means engaging with the attackers. Internal IT teams are likely to find themselves ill-equipped to deal with the technical demands made by an attack. The orthodox advice is for companies to seek out a reputable incident response company to advise and conduct the communications.

That done, many advisers suggest a “dual path” once dealing with a ransom demand: scope out the potential for restoration of data from backups or other sources, while at the same time beginning communication with the criminals. If one process goes wrong a victim company can fall back on the other without having to start from scratch, says Bill Siegel.

Scoping the project is a critical step. Restoring data could be painfully expensive. Building a picture of what data sources are left to work with (one option is the use of emails saved locally on individual machines), and the way it might be restored, can give a fairly good estimate of how much it might cost. That can then be compared with the price tag criminals have placed on releasing and decrypting computer files.

Legal consequences

There is also another set of factors to consider before signing off on payments to the criminals: the legal consequences. There is no legal prohibition against paying a ransom. It comes down to a judgement involving the criminal and the victim. But there are legal implications to consider as a result of a ransomware attacks that may play a part in deciding whether to give in to demands.

According to Mark Deem, data inaccessible due to ransomware could mean failing to deliver promised work or services. That could place victims in the position of being in breach of contract. From a business position that could also mean losing commercial relationships, another considerable cost. Though it is possible, depending on the terms of a contract, that a cyber-attack could give a company a valid defence. That, however, would need to be established through a review of contracts.

It is also worth considering that an attack is likely to cast a shadow over the reputation of a company over time, even if resolved. According to Deem, in the event of a significant deal, such as a merger or acquisition, the details of the attack and the remedies undertaken post-resolution would need to be disclosed.

Some victims may find themselves with with very particular risks and potential liabilities. Steven Windle says hospitals could face the appalling risk of causing death if they fail to pay up.

Major regulatory implications also present a risk. An attack could place a company in contravention of GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation). This grim outcome results if the subjects of personal details held on computer systems held by a company cannot access that information. “If you hold that personal information, and you’re effectively denying the data subject access to it, that is a potential breach,” says Deem.

This, he says, is a critical issue. Many companies have done their homework and prepared for compliance with the demands of GDPR. But cybercrime holds a bigger threat.

“With organisations’ intensive focus on GDPR and especially personal data leading up to 25 May 2018, there may now be a less heightened state of awareness of the potential damage which could be caused by a cyber-attack, which strikes at the heart of their IT network and may well extend beyond purely personal data,” says Deem.

If a company does move to paying a ransom demand, there is one last chilling implication to consider: the possibility of terrorism.

Although a ransom payment is not illegal in itself, if a payment is made and it ends up with a terrorist organisation a company could be in contravention of Section 17 of the Terrorism Act.

“To the extent that you can,” says Deem, a company and its board have to assure themselves there are no indications of terrorism in the ransomware attack, a process that can be fraught with uncertainties given the murky way attackers communicate and obscure their identities.

Keeping the authorities informed and updated on the developing negotiations is one way of building a defence should there be allegations relating to terrorism later.

Paying up after ransomware attacks

The early stages of an attack and communication with the attackers is an important moment to assess the attackers’ objectives. Steven Windle, Accenture’s cyber investigations and forensic response lead in Latin America and Europe, says an attacker’s motive may be financial, but it may not. It could just be about destruction.

“It’s important to understand the objective as this will determine whether the attacker is serious about returning the data,” he says.

Once the decision to pay is made, there is broad agreement that a specialist should take over the process of communication with the criminals. Contact can take place at odd times of the day and, though often by email, can also involve messages across the Dark Web on so-called Tor sites, shadowy outposts on the internet that allow untraceable and anonymised communication between parties. The Tor site could also be the location for virtual wallets where victims will send their Bitcoin ransom payments.

Specialists also come to know the attackers over time by monitoring the tech they use and their favoured patterns of communication and behaviour. Bill Siegel estimates that fewer than 100 groups are responsible for the majority of global ransomware attacks. Knowing the group’s modus operandi and past history can help experts gauge how a negotiation is likely to play out. That, in turn, helps with the comparison against restoration costs.

—Bill Siegel, Coveware

Once contact is made there comes a crucial moment in the process that helps assure negotiators that the cybercriminals can do what they claim: the “proof of concept”.

This is the equivalent to the “proof of life” moment in a kidnapping scenario. With proof of concept, the attackers prove they can decrypt sample files sent to them by the victim company’s advisors. This proves they have the means to decode the missing data, though at that stage it may not give a full picture of how much is recoverable post-decryption. Siegel warns that companies should consider they are dealing with highly sophisticated operators, whose businesses centre on the internet and data aggregation.

“You’re not being targeted even by a group,” says Siegel, “you’re being targeted by an industry and your data is the method by which they monetise their business. And it is a large industry, highly specialised and globally distributed. It has a specialised means of communication, logistics, coordinating, trading, cash movement, clearing and settlement of goods and services: It has all the hallmarks of an industry.”

It is the stuff of business nightmares. There is broad agreement that settling with cybercriminals should be avoided, if at all possible.

Peter Groucutt makes the point emphatically: “Paying ransomware should absolutely not be the first choice. Paying ransomware encourages more of the activity and funds further cybercrime. It should only be entertained if it is not possible to recover from backups.”

That said, it has become inevitable for many companies. Digitisation of business has expanded the number of potential targets and given the criminals greater leverage. That places a premium on being prepared.

According to Steven Windle: “An organisation should have an incident response plan prepared for a ransomware attack and practice it by running through various simulated scenarios.”

This sort of exercise will give companies an idea of the right personnel to be involved from the beginning. Windle says this could vary depending on the sector a business is in (see box below for considerations).

Bill Siegel says there is a growing recognition that corporate incident response plans should include the possibility of paying a ransom. That’s depressing news. But boards should prepare. Business who fail to do so could pay the ultimate price.

“For the victims it’s incredibly stressful,” says Siegel. “You picture a company where people went into the office expecting a normal day and then they realise the gravity of the situation, some of them realise the company could fail. And we’ve seen it. We’ve had to handle cases where the end result was bankruptcy.” That should be a warning to everyone.

Considerations for managing ransomware attacks

By Steven Windle, Accenture

- The security team (incident response) should be involved to run the investigation, identify, understand, contain, and eradicate the problem. If a company lacks internal resources, or is overwhelmed by the scale of attack, an external IR provider may need to be brought in. The benefit of this is not just deep technical expertise, but also extensive experience of dealing with ransomware cases across various industries.

- An IT manager is required if it is determined that workstations or endpoints must be rebuilt, rather than restored, and to validate with critical systems and whether they have been impacted and if there are any backups.

- The board should be involved from a strategic and crisis management perspective.

- Depending on the scale of infection, involvement of multiple business units may be necessary: HR, Legal, Health & Safety. For example, legal needs to be involved if PII has been exposed, communications may need to be involved to handle reputational damage and interaction with media.