Last week news outlets were filled by stories of Twitter’s clash with Donald Trump over the president’s tweets. While somewhat overtaken by recent events, the collision highlights how corporate leaders have felt compelled to step in to the political arena to both defend corporate reputation and, as commentators often observe, fill the void left by political actors.

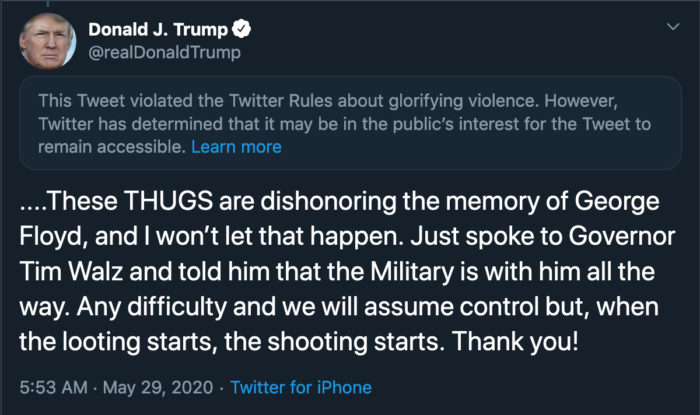

The conflict began with Twitter’s decision to add warning labels to three of President Trump’s tweets. The first two, on 26 May, involved adding a “fact checking” warning to claims made by the president that postal ballots would lead to voter fraud. The next involved a declaration attached to the now notorious Trump tweet in which he proclaimed that “when the looting starts, the shooting starts”. Twitter’s label said the president’s message “violated” the social media site’s rules about “glorifying violence”.

Trump was furious and responded with an executive order “cracking down” on social media sites with amendments to a key piece of US legislation, section 230, the law which absolves platforms of liability for the content users post.

The amendments will affect other sites too, including Facebook, whose founder and chief executive Mark Zuckerberg has argued fervently that it should not be the role of platforms to censor users.

The episode leaves Twitter in a compelling face-off with the president and a demanding corporate governance issue for its chief executive Jack Dorsey—and his board—to handle.

That it is an urgent governance issue is underpinned by the capital structure of Twitter compared with Facebook. As corporate governance expert Professor Richard Leblanc points out, Facebook has a dual-class share structure giving Zuckerberg enormous power. Twitter does not, making Dorsey more accountable to his board.

But the intervention also places Dorsey in the realm of “activist CEO”—a company leader making a stand on political or social issues.

CEO activism on the rise

The US has seen much of this in recent years as elected leaders remained silent or swung away from core political concerns. “As the global challenges keep piling up, CEOs are becoming the bullhorns of democracy,” wrote US academics Caroline Kaeb and David Scheffer in June last year.

Examples are numerous. Following school shootings in 2018, many retailers took guns off their shelves and distanced themselves from the National Rifle Association (NRA). Following the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi, chief executives from all over the world boycotted a conference in Saudi Arabia billed as the “Davos in the desert”. May last year saw the leaders of 13 US companies help found the CEO Climate Dialogue as part of an effort to shift government policy on the environment.

Netflix became the first company to join legal advocacy groups in challenging the state of Georgia’s efforts to curtail female reproductive freedoms. Elsewhere, Nike famously featured the football player Colin Kaepernick in an advertising campaign. Kaepernick had outraged some in the US with his refusal to stand for the national anthem in protest at police brutality against African-Americans.

These are all conscious decisions. While moves such as these are risky, they can pay off. Despite provoking a backlash, the “buzz” surrounding Nike and Kaepernick was estimated to be worth $163m in marketing value. Though, marketing benefits are not the only reason. Companies are allowed to do the right thing, not least because their employees and customers will reflect the diversity within society.

It may help that despite corporate scandals and the financial crisis of 2008, trust in politicians is lower than it is in company leaders. The 2020 Edelman Trust Barometer found that while 51% of those polled for the survey trusted CEOs, only 42% trusted heads of government. A huge 87% said stakeholders were more important than shareholders to long-term company success while 92% of employees believe it is important for CEOs to speak out on social issues.

However, it is worth noting that Twitter’s situation is different in quality to the CEOs in many of the examples cited here. What makes Dorsey’s position so unique is that while most activist CEOs make moves on issues somewhat removed from their company operations, Twitter’s intervention was about the way its own services are used.

In short, the company’s reputation was at stake. A CEO and a board cannot ignore that indefinitely.

“Twitter is a teachable moment for board discussions with management on pushing back when politicians take steps that harm the reputation and goodwill of the company,” says governance expert Leblanc.

Twitter’s action may well prompt other CEOs to take similar stands, especially when political actors play fast and loose with the truth. “A company CEO would never have the unlimited speech that bad political actors have. There should be greater accountability for political speech,” adds Leblanc.

Social media law

Mark Zuckerberg now has his own leadership concerns after staff and civil rights leaders chose to protest against his refusal to follow Twitter’s lead. Whether there is enough momentum to force a change of heart remains to be seen.

But the fact that Facebook and Twitter are at odds over an issue so critical to the functioning of contemporary society means Section 230 probably needs be reformed, according to Leblanc. As it stands the law is not enough to help boards in social media firms to steer a clear path through the complex questions raised by freedom of speech, fake news and the needs of a functioning society in general.

Outside social media, other corporate leaders will be watching what happens. Twitter’s example may give them courage to chart their own course into activism.

In the end, the way social media companies respond to content may come down to governance structures, as mentioned earlier. Carum Basra, a policy adviser at the Institute of Directors, says: “Ultimately, for many of these entities it will be for their boards to determine where to draw the line in terms of what is acceptable.

“However, some of these firms have governance structures that concentrate power in the hands of one or two individuals; more boardroom challenge might be what is needed.”