One thing that provokes the ire of Fiona Reynolds, managing director of Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), is when company directors tell her they’ve had no questions from their investors about environmental, social and governance issues.

As she speaks to Board Agenda, it’s quite clear the issue leaves her stewing, but she is also quick to point out that many companies have responded to investor engagement on ESG and are making changes. That said, the journey on ESG is not yet complete.

“There’s a lot more to be done and sometimes I get frustrated,” says Reynolds, “when I speak to company senior executives, or company boards, and they say to me: ‘I know you’re talking about these sustainability issues, Fiona, but nobody is asking us questions about these issues’.”

As far as Reynolds is concerned, it’s all about the alignment of interests: investors define their interests correctly and communicate them clearly to company boards, which persuades them to address ESG in a substantive way.

This is important because last year, PRI celebrated ten years since its inception to persuade the investment community that it had to press for its investee companies to incorporate ESG factors in their strategies and business models.

And the theme that crops up time and again in conversation with Reynolds is that the campaign is having an effect, investors are listening and changing their ways—but there’s an awful lot more work to be done before the PRI does itself out of a job.

Changing the ways of investors

Reynolds joined PRI in 2013 and has been working on changing the ways of investors since then. Before PRI she was chief executive of the Australian association for asset owners, the AIST, and in 2012 was named by the Australian Financial Review as one of the country’s top 100 women of influence for work in public policy.

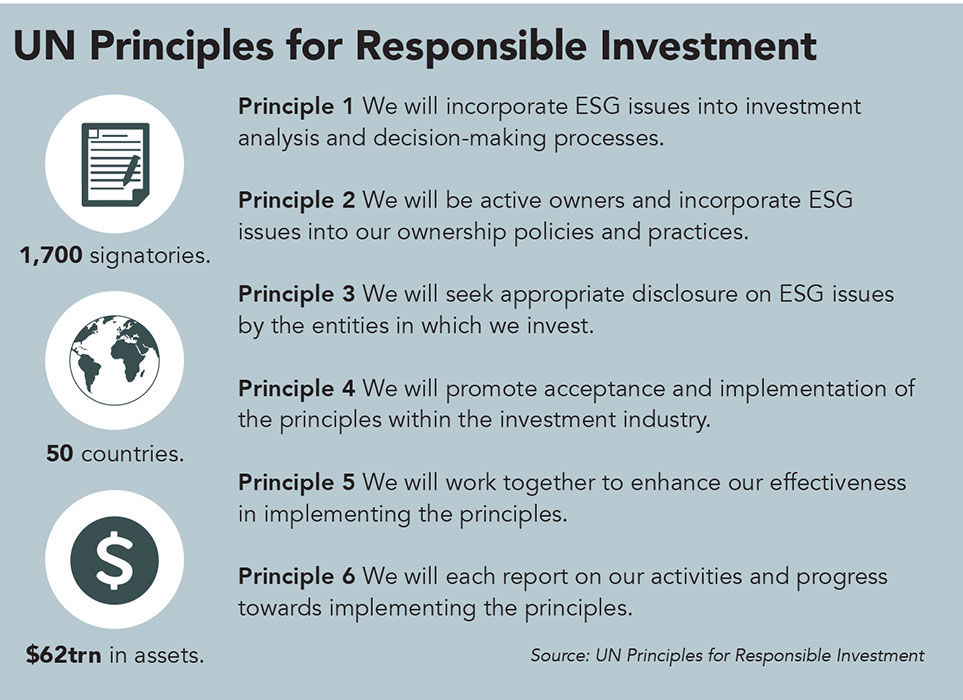

The PRI was set up in 2006 with the support of the United Nations, but it is not a UN body. Many of its directors are elected by asset owners and it has two permanent UN advisers. As you might expect, 2006 involved only a small group of asset owners, but ten years later the PRI has 1,700 signatories—with $63trn under management—to its core six principles.

Reynolds points out that not all of those assets are managed in a way that is “sustainable”, but some of the portfolios are extremely large and take time to transition. She is happy, however, to say that one of the PRI’s missions is to do itself out of work.

“If PRI was to be truly successful,” she says, “then you wouldn’t need the PRI because we wouldn’t have to talk about responsible investment in a way that’s separate from investments, which we still do.”

What the PRI seeks is that investors integrate ESG considerations into their mainstream thinking about investment, so that it is no longer an add-on or an adjunct. That will, however, take time.

“Sadly, I think that the PRI will still be around for at least another decade and probably a few more decades after that,” says Reynolds.

Power of six

The PRI’s core principles cover a range of areas but at its heart is a commitment to incorporate ESG issues into investment decisions and analysis (see box, above). There are five others but they build on that first principle that ESG is what guides the decision-making process.

Investors in northern European countries have adapted well but those in the US and Asia are behind the game. Asia’s issue concerns being a developing market working with “deferential” cultures.

There are, however, big governance and stewardship changes underway in Japan driven by prime minister Abe’s efforts to shake up the country’s corporate world and attract foreign investors. Reynolds points out that courting European investors means acknowledging their governance needs.

The US, too, has been slow to move but Reynolds observes that it is changing, with investors there making progress. The demands of European clients have seen to that, but the Paris agreement on climate change has also played a part in causing investors to “sit up and take notice”, she says.

The involvement of Mark Carney, governor of the Bank of England, by promoting guidance produced by the Financial Stability Board’s task force on climate change disclosures, has also persuaded investors that there are “material risks”, and that they must be considered.

“I think there’s been some very strong market signals in the last couple of years,” says Reynolds, who praises Carney for winning front-page headlines for the issue that has helped trigger recent attention. “On the one hand it’s good. On the other, it’s frustrating that it takes some investors a lot longer.”

Sustainable systems

The big agenda on the horizon for PRI is its project on a sustainable financial system. Reynolds says there has been much work on how investors relate to companies, but if things are to really change, if there is to be widespread improvement, the “system” needs to be tackled.

“You need to do more than think about the ESG in a company,” she says. And this is about aligning the interests of investors who invest for the long term, perhaps decades at a time. PRI will study what needs to be done to make systems sustainable.

Reynolds says that there will be a raft of issues at the heart of the project: executives incentivised with short-term rewards and staying in post for an average of around five years; the kind of mandates given to asset managers and ensuring they’re not judged against short-term performance measures; the way portfolio managers are rewarded for short-term gains; reporting structures that are not just about the bottom line and cash flow and the next set of quarterly results; and also the effect technology may be having on the way shares are owned.

These are all important for investors but also important for a general public that has lost a lot of faith in the way big business is run and who it is run for. And what’s driving much of the interest in ESG is the public asking hard questions about the purpose of big, multinational business.

“If you look at a lot of the things happening in the world today, there’s definitely a lot of social and political polarisation going on,” says Reynolds. “That’s because people feel that the political system and the financial system doesn’t work in their favour.

“They read about CEO pay, they read companies aren’t paying their taxes even though they are making a fortune … and at the same time they’re told they’re going to have all this belt-tightening following the global financial crisis, that we have to cut services and that wages can’t go up to match inflation.

“It’s no wonder that there is this frustration and perception that the financial system works for a few, not for the majority.” She adds: “And when you think about whose money is invested in the system, a large amount of it is people’s pension fund money.”

Other issues on the horizon

PRI is also about to start a project about the sustainability of water supply and how that should feed into investment decisions—a big question facing thirsty companies that use vast quantities for production purposes. But Reynolds sees ESG issues evolving in the future. Which means we have other issues to contend with on the horizon.

“If you look at the issue of cybersecurity, that wasn’t really on our radar as an ESG issue maybe five years ago. Now, in terms of governance, it’s one of the biggest risks that companies and investors think about.

“Investors are also starting to think about issues like robotics, the Internet of Things, and artificial intelligence, what it means for investments and whether they raise ethical issues.”

Reynolds also raises the issue of antibiotic resistance that has many medical experts worried. “That’s a huge health issue for people and for the world, so I think the ESG issue will just continue coming to the fore.”

Just as Reynolds said, it looks like the PRI has work enough for years to come.