Business has lost the public’s trust. CEO pay and profits are soaring, while ordinary incomes have stagnated but global temperatures have not. As a result, while politicians used to campaign on health and education policy, the real vote-winner these days is promises to crack down on business.

So it’s urgent that boards take action. If they don’t, not only may customers and workers walk away, but also politicians may pass regulations that overturn capitalism as we know it. For example, Labour’s proposal to confiscate 10% of company shares would be the biggest expropriation of private property in the UK’s recent history.

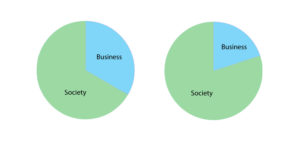

But some of the actions that the public are proposing may not actually be in the best interest of society. Many are based on the pie-splitting mentality. They see the value that a company creates as a fixed pie. Thus, the only way to increase the slice enjoyed by society is to reduce the slice that goes to business—slash CEO pay, restrict dividends and share buybacks, and donate profits to eye-catching corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives. Indeed, any reforms that downplay investors or reduce their rights are wildly applauded. In contrast, high profits are shamed, as if being successful is something to be embarrassed about.

Business and society

But viewing the relationship between business and society as a fight between “them” and “us” is deeply flawed. For example, investors are not nameless, faceless capitalists but include ordinary citizens saving for retirement, or mutual funds or pension funds investing on their behalf. They are not “them”, they are “us”. So while it’s critical for companies to take very seriously their responsibility to society, this shouldn’t be a licence to cheerfully ignore investors.

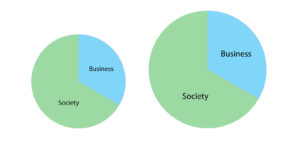

That’s the power of a different approach to business—the pie-growing mentality. This mentality stresses that the pie is not fixed. Under this approach, a company’s primary responsibility is to grow the pie—to create value for society. Critically, doing so increases profits as a by-product, so profits aren’t evil value extraction but instead a result of serving a social need. A company may develop a new drug to solve a public health crisis, without considering whether those affected are able to pay for it, yet end up successfully commercialising it.

Importantly, the idea that both business and society can simultaneously benefit is not a too-good-to-be-true pipe dream, but one backed up by rigorous evidence. One of my own studies shows that companies with high employee satisfaction outperformed their peers by 2.3–3.8% per year over a 28-year period—that’s 89–184% compounded. Further tests suggest that it’s employee satisfaction that leads to good performance, rather than the reverse. A pie-growing company improves working conditions out of genuine concern for its employees, yet these employees become more motivated and productive, ultimately benefiting investors.

What does this mean for boards? The primary way to reform business is to positively create value for society, rather than to sacrifice profits. As an example of how this shifts our thinking, Vodafone was the first telecoms company to launch a tax transparency report on how much they were paying to governments worldwide out of profits. Being a responsible taxpayer is certainly important. But paying tax is not the primary way a company serves society. Instead, Vodafone made a far greater contribution by launching the mobile money service M-Pesa, providing banking to the unbanked and lifting 200,000 Kenyans out of poverty. The role of boards isn’t just to ensure companies pay fair tax, or even fair wages, but that they innovate and create products that transform customers’ lives for the better.

Purpose shapes decisions

Central to the pie-growing mentality is for companies to be driven by purpose. Purpose is why a company exists, its reason for being, and the role it plays in the world. It answers the question “how is the world a better place by your company being here?” Purpose is fundamental to a company’s core business, unlike CSR which often involves non-core, profit-sacrificing activities to apologise for the harm created by its central activities.

But almost all companies have a purpose statement. How do boards ensure it’s put into practice? I’ll offer three suggestions. The first is to ensure that purpose shapes decisions—that executives take different actions than they would have without a purpose. For example, CVS didn’t just define their purpose statement as “helping people on their path to better health”, but stopped selling cigarettes in 2014 even though they generated $2 billion in sales. CVS’s sales rose from $139 billion in 2014 to $185 billion three years later, so this decision wasn’t at the expense of profits. Relatedly, the board shouldn’t allow executives to propose an M&A deal, strategic initiative or major capital expenditure without explaining how it’s consistent with the firm’s purpose.

The second is to ensure that purpose is targeted. A purpose statement can’t be all things to all people. One that aims “to serve customers, colleagues, suppliers, the environment, and communities while generating returns to investors” sounds inspiring. But it ignores the reality of trade-offs, instead sweeping them under the carpet, and thus provides no practical guidance on how to navigate them. If shutting down a coal-fired power station helps the environment but hurts workers, does it further the above purpose statement? It’s not clear. Instead, an effective purpose highlights which stakeholders are first among equals. Energy company Engie closed down Hazelwood, the most polluting plant in Australia, even though doing so made 750 workers redundant, because it had decided to prioritise transitioning to low-carbon energy. After taking this decision, it then endeavoured to find these workers other jobs. But its purpose had made it clear what it had to do.

The third is to ensure that purpose is monitored. This involves setting relevant targets, such as Marks & Spencer’s 150 “Plan A” goals, and holding executives accountable for progress. But monitoring shouldn’t just be quantitative. Many of the key issues that affect stakeholders—and thus ultimately benefit investors—are qualitative, which is why purpose should be “monitored”, not “measured”. Fair pay is certainly critical to workers, but so are meaningful work, skills development, and the freedom to speak up. Directors should ensure they are sufficiently informed on these issues—by walking the shop floor first-hand, hearing the insights of stakeholder panels, or challenging executives. Doing will keep them informed on not just what can be measured in an organisation, but also what matters.

Alex Edmans is professor of finance at London Business School. His new book Grow The Pie: How Great Companies Deliver Both Purpose and Profit is currently available for pre-order.