If there’s a company in the UK that conjures up the essence of service to customers it is Marks & Spencer. Famed for its comfy underwear and high-quality food, M&S is an iconic brand known for its commitment to customers and, through its much-praised Plan A, a devotion to sustainability.

Much of the delivery of Plan A has happened under the watch of Robert Swannell, the department store’s chairman until September 2017.

Having led the board since 2011, Swannell has not only seen M&S’s development as a sustainable business, but since the financial crisis he has witnessed the business world grapple with going beyond its narrow interest in making money to playing a more significant role in the world.

As he leaves M&S, however, he does so believing that things are on the right track, that much has been achieved and there is more to look forward to.

“I’m actually pretty optimistic,” he says. “Businesses do understand where they fit into society, and the events of the last decade have only served to emphasise that.

“Ultimately, the only thing that creates wealth and improves the lives of everybody in the world are businesses, so it’s in everybody’s interests that we get it right.”

Leading on sustainability

Swannell has been with M&S for 16 years, joining the board after 33 years in investment banking with Schroders and Citigroup. The company was already one of the country’s most respected high-street occupants, but Plan A, launched in 2007, saw M&S take the lead in sustainability.

It was not that other companies were ignoring sustainability, but with Plan A, M&S gave it a level of public importance that had not been seen previously among high-profile brand names.

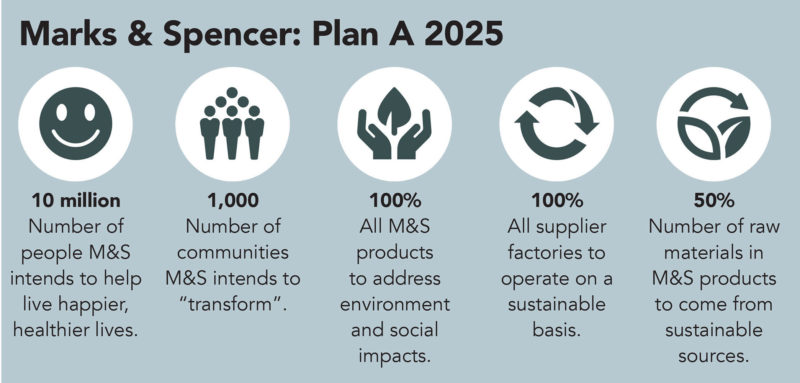

In January this year, Plan A was rebooted with a fresh set of aims and objectives. And they’re not exactly minor ambitions. The company says on its website: “We’re determined to play a leading role in the years ahead: helping to build a sustainable future by being a business that enables our customers to have a positive impact on wellbeing, communities and the planet, through all that we do.”

To that end M&S’s aims include: “Help 10 million people live happier and healthier lives”; “be the world’s leading retailer on engaging and supporting customers in sustainable living”; and “undertake a range of activities to identify how our stores and people can make a positive and measurable difference to their neighbourhood.” The retailer intends to roll out that latter one to a thousand communities.

M&S likes to think big on sustainability and it likes to make it public.

Swannell, too, has been speaking out, demonstrating his reflections on the state of corporate leadership. When think-tank Tomorrow’s Company launched a report in June claiming that UK boards have become bogged down in risk mitigation and compliance monitoring, rather than supporting executives in investing for the long term, Swannell lent his support, with a nod towards companies needing to resolve their purpose. The report, he said, would help boards “step back and decide what they are there to do and how they add value.”

He added: “This isn’t just more process. It reflects the reality that boards will have a different focus at different points in the lifecycle of a company.

“The work of the board will also reflect the capabilities of the executive team and the dynamic between chairman, NEDs and CEO. No two companies are alike and governance must address the reality of each individual company.”

Beyond shareholder value

So what is the state of the boardroom? Swannell is optimistic about where things stand, but explains that companies must see further than “shareholder value”.

Speaking to Board Agenda, he says: “I have a strong view that companies need to be connected with society. So they have a wider duty than a simple metric of shareholder value.

“This is not in conflict with looking after the interests of shareholders because, in the end, companies will, in my view, only succeed if they are given a licence to operate by the people whose lives they affect. And that includes customers, employees, suppliers and actually the communities in which they trade.”

He adds: “Boards need to explicitly understand that, and make it part of their leadership; certainly at M&S it is an integral part of what we do and what we’re about.”

But in general, are companies getting culture and values right? Swannell points out that each time there’s an all-too-frequent corporate scandal, culture and values are among the features that have gone wrong. He also recognises that mastering culture and values inside an organisation is not the easiest management discipline. However, he adds: “The fact that it’s difficult to measure doesn’t mean that it isn’t valuable.”

“There are lots of different ways you can measure it,” he says, “either by observable metrics or simply by asking the right questions and talking to people,” he says.

And that takes us to trust, which Swannell says is a critical issue. Lose it and the company may be lost. That’s why M&S thinks long term. Strategies such as Plan A are a differentiating factor that underpin the trust customers have in the brand and in the company.

“It is part of being a successful business for the long term and not just worrying about quarterly like-for-likes or quarterly profit margins which, of course, is important,” says Swannell. “But, ultimately, you can miss or make a mistake in business; if you fundamentally lose people’s trust, it’s much more damaging and long lasting.”

Board quality

Of course, much of how a company functions relies on the quality of the board. Tomorrow’s Company is worried that boardrooms are swamped by risk management and regulation—major distractions from the business of formulating long-term strategy. Swannell observes that boards have to do both: comply with regulation and make strategic decisions. But the balance can be tilted.

Spotting the problem is the issue. Swannell says “rigorous” board evaluations are the answer, where all parties “either affected by how the board behaves, or the board itself”, can speak their minds candidly.

Regulators like the Financial Reporting Council have taken a close look at culture, and a review of the UK Corporate Governance Code could include changes that will address the issue. And while Swannell doesn’t see any great need for regulatory action, he does believe boards should always be looking for ways to improve and refine their governance measures.

At M&S there is now an employee organisation that speaks regularly to the board, thereby offering a new structure for private shareholders to air their views. This, says Swannell, gives the board important feedback. “There are lots of ways that boards can move the dialogue on and…assess whether they are doing a good job.”

And stakeholders are important. Swannell says one institution he instigated at M&S was to hold meetings with institutional shareholders, the chairman, the chairs of the audit and remuneration committees as well as the company secretary and the director in charge of Plan A, to discuss strategy, company purpose, board evolution and culture.

“Shareholders should be interested in that as well as the nitty gritty of sales and margins and profits and everything else. There are some examples of shareholders who really add value as owners, and there are some who, frankly, are less good and benefit from the activity of the active and engaged shareholders. I think that’s a shame.”

Embracing change

While the nature of the issues facing boards has changed dramatically in recent years, they are set to change again as artificial intelligence (AI) and other technologies like robotics become cheaper and more widely available. Are boards equipped to confront the rapid pace of change? Swannell says non-executives must be “infinitely curious” about developments around them.

“Every single non-exec has got to be interested by what’s going on in the digital world,” he says. “You can’t understand the business that you’re working with if you are not looking around you for what’s going on. You simply couldn’t be a non-exec in the current environment without that mindset.”

The warnings about the effect robotics and AI might have on society have been numerous and highly publicised. Others have observed that, properly managed, the transition to the next stage of technological development will be a benefit to everyone. One thing seems certain: the new technology will cause upheaval.

In some ways, the financial crisis provided a similar event, acting as a catalyst for rethinking what business is for. Dramatic events like that can be useful.

“Periodic shocks to the system aren’t a bad thing,” Swannell says, “as long as everybody remembers what it is we’re in business to do, which is obviously not only to be successful businesses, but to play our part in society as well.”

Supported by Mazars Business. For Good—interviews on thinking and acting long term to enhance business performance.