J P Morgan Chase’s chief executive and chair Jamie Dimon has been touted as a potential US presidential candidate, but anyone scouring his annual letter to shareholders for evidence of political ambitions will have found the boss of one of the world’s biggest banks has more pressing concerns.

“[Poor] cybersecurity may very well be the biggest threat to the US financial system,” Dimon said in April. The company revealed in its most recent annual report that it spends around $600m a year on its efforts to protect its business and customers, and has more than 3,000 employees dedicated to cybersecurity.

Big banks are spending billions of dollars to tackle cybersecurity and regularly test the resilience of their systems using “ethical hackers” who are tasked with testing their systems to breaking point.

But while banks are making progress in recruiting the right talent, there is considerable regional variance and room for improvement, according to a survey of US and European banks by Aktis, a leading provider of bank governance data.

Big financial institutions need to ensure they have an overarching view of one of the growing risks facing their businesses. Recessions come and go, but a cyber-attack that compromises the data and wealth of a bank’s customers could capsize its share price and hole its reputation permanently below the waterline.

With increasing levels of digitisation, widespread access to banking services and the advent of new computing techniques, cyber-attacks could lead to technology failures, security breaches, unauthorised access, loss or destruction of data or unavailability of services—all of which would be catastrophic for shareholder value.

Failures are damaging, whether or not they are a result of malicious intent, and they go beyond the scope of a technology problem. In April 2018, TSB customers were locked out of their accounts and some gained access to other people’s details when the UK lender’s migration to a new IT system hit problems.

The incident prompted a parliamentary inquiry and reached all the way to the boardroom, with the bank’s CEO Paul Pester eventually stepping down. Meanwhile, the bank’s balance sheet was as battered as its reputation, with TSB reporting an annual loss for 2018 after spending £330m to address the IT failure, including fraud and operational losses of £49m.

In an increasingly connected world, cyber-attacks can be devastating and with hackers becoming ever more sophisticated, banks are vulnerable. So while it’s hard to plan for every eventuality, boards must ensure they have the right level of expertise and control so that they prevent attacks where possible and, where not, formulate an adequate response and action plan.

But in this rapidly evolving area, what does best practice look like and how do bank boards in the US and Europe ensure they have the right approach—and the expertise in place—to meet the challenge? How can they ensure investment dollars are allocated in the right way? And how can boards monitor progress while setting the tone for cybersecurity in a way that all employees understand and relate to?

Expertise and experience

Banking is one of the more advanced industries when it comes to cybersecurity. Within banking, there is a convergence between cybersecurity, anti-money laundering (AML) and fraud issues as part of big banks’ Know Your Customer (KYC) programmes.

These areas are usually the responsibility of chief information officers, although they are sometimes too focused on day-to-day operations. At a time when banks are engaged in an arms race for digital dominance, cybersecurity is an issue that should be owned by the business.

Despite the large volume of investments in cybersecurity, bank boards are still lagging when it comes to their own expertise. In order to move towards a model of best practice, the first challenge is to ensure that boards have the right level of knowledge by appointing non-executive directors with expertise and preferably executive experience in the field of cybersecurity.

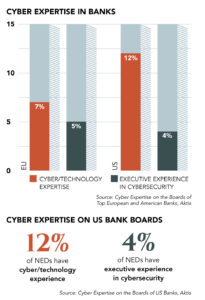

The Aktis research looked at the number of non-executive directors on bank boards in two areas: those who have held full-time executive positions with responsibility over matters of cybersecurity, and those with knowledge of either cybersecurity or technology.

Aktis found that of 30 of the biggest US banks, only 4% had non-executives on their board with prior executive responsibility for cybersecurity. Only four—Citigroup, Morgan Stanley, State Street and Bank of New York Mellon—had established technology committees.

In 2017, only one US bank provided cybersecurity training to its board and there is currently no stand-out example of best practice.

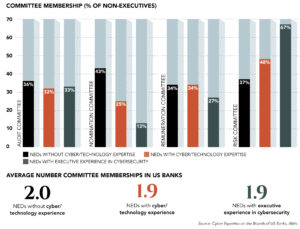

Among the sample of US banks, more than two-thirds of the non-executives with executive experience in cybersecurity served as risk committee members in 2017, meaning that their experience is deemed to add value to the work of risk committees, according to Aktis.

More than two-thirds of non-executives with executive experience in cybersecurity roles have a board tenure of five years or less, showing that the focus on boosting expertise is a recent phenomenon. By contrast, NEDs without cyber or technology expertise have an average tenure of nine years.

In Europe, banks face a welter of regulatory issues in an industry that is in flux. The introduction of GDPR in 2018 has placed a greater emphasis on compliance with cybersecurity policies.

In Europe, banks face a welter of regulatory issues in an industry that is in flux. The introduction of GDPR in 2018 has placed a greater emphasis on compliance with cybersecurity policies.

Meanwhile, the rise of digital banking poses fresh challenges to customer security. The emergence of open banking and the introduction of the second Payment Services Directive throws up questions about the security capabilities of new market entrants.

Local regulators are also focusing more on cyber and operational resilience. In the UK, the Financial Conduct Authority is engaging in ongoing discussions about systemic risk associated with cloud services.

Perhaps as a result of the more dynamic regulatory environment in Europe, its financial institutions are ahead of their US peers when it comes to board expertise. Research into 30 of Europe’s biggest banks by Aktis shows that 12% have NEDs with prior executive responsibility for cybersecurity.

Six European banks provided cybersecurity training to their boards in 2017, compared with one in the US. Three European banks—BBVA, Banco Santander, and Royal Bank of Scotland—have dedicated technology committees, although only BBVA’s has “cybersecurity” in the title.

An evolving approach

Typically banks maintain three lines of defence when it comes to cybersecurity: technology, comprising the chief information security officer (CISO); risk; and internal audit. Under this model, the CISO acts as overall gatekeeper. But this approach is evolving.

“Since the financial crisis, supervisory authorities have nudged banks to transfer responsibility for cybersecurity from the audit committee to the risk committee,” says Stilpon Nestor, founder and CEO of governance advisory firm Nestor Advisors. “As a result the risk committee is replacing the audit committee as the second line of defence.”

“Since the financial crisis, supervisory authorities have nudged banks to transfer responsibility for cybersecurity from the audit committee to the risk committee,” says Stilpon Nestor, founder and CEO of governance advisory firm Nestor Advisors. “As a result the risk committee is replacing the audit committee as the second line of defence.”

Having one committee with overarching responsibility for all aspects of risk and compliance may constitute a neat solution for regulators, but is it the right approach for banks themselves?

“The audit committee is equipped to look at breaches of compliance and fraud, while the risk committee is more focused on overall operational and credit risk at the bank. Moving towards a model where these are under the same roof may not be the optimum approach,” says Nestor.

Banks vary in the approach they take to cyber-risk and the model they choose is shaped by where the expertise lies. There is, however, a conundrum for boards: individuals with narrow cyber expertise do not always possess the broader board-level experience to contribute adequately as non-executives.

—Stilpon Nestor, Nestor Advisors

“Simply hiring a non-executive because they have cyber expertise runs the risk of undermining good governance,” says Nestor. Moreover, since the financial crisis, boards have become smaller and more nimble, but the race to hire talent with expertise in cybersecurity could lead to bloated boards.

In some cases, a better solution may lie in creating an external advisory board, which meets twice a year and provides counsel to the main board.

“Cybersecurity is first and foremost an issue for the business to manage and for the senior management team to get its arms around,” says Nestor.

The business is the first line of defence, so having the right chief technology officer and risk committees in place is crucial. One approach, which has been adopted by Spanish banks Santander and BBVA, is to embed cybersecurity as part of the strategic dialogue at executive board level. “Then cybersecurity becomes part of digitisation strategy and banks can look at opportunities as well as threats,” says Nestor.

This ultimately enables the business to make decisions about new products, services and channels and weigh the strategic risks as they would for other areas of the business.

By adopting this approach, businesses can make cybersecurity decisions based on in-depth assessments of all risks— including regulatory risks—and therefore make more solid arguments and disclosures regarding compliance to regulatory authorities. This will create a more holistic approach to tackling the changing nature of operational risk in an increasingly digitised industry, and help banks to develop robust technologies that provide business solutions.

A culture of resilience

There is no silver bullet when it comes to best practice. Banks should base their approach to cybersecurity according to their expertise.

As a rule of thumb, those that have long-term management teams and demonstrated resilience during the financial crisis have a deep culture of understanding risk, and may not need to overhaul their operations. But it is not necessarily the job of the board to own the issue of cybersecurity and impose it on the business.

More than any other industry, banks have a risk management culture that should serve as a solid foundation for tackling cybersecurity. For example, no bank fell victim to the criminal ransomware NotPetya and WannaCry that affected many industries in 2017.

But more needs to be done to ensure that individuals take ownership of cybersecurity. And this does not just apply to potential rogue employees or lower-ranked staff members. In 2017 Barclays CEO Jes Staley and Bank of England chief Mark Carney both fell victim to email hoaxes, showing that breaches can occur at the very top of an organisation.

Last year the Bank of England and the Financial Conduct Authority said in a discussion paper that banks must be alive to operational risks and cyber-threats that could weaken financial stability, threaten the existence of individual firms or hurt consumers.

FCA chief executive Andrew Bailey, Jon Cunliffe, the Bank of England’s deputy governor for financial stability, and Sam Woods, who heads the central bank’s Prudential Regulation Authority, wrote: “The financial sector needs an approach to operational risk management that includes preventative measures and the capabilities—in terms of people, processes and organisational culture—to adapt and recover when things go wrong.”

The report made it clear that they want to see banks assuming that IT systems will go wrong at some point, and building backups. Rather than pursuing the impregnability of individual systems, they said, financial institutions should focus on ensuring the services they offer to customers are maintained, by whatever means.

Strengthening operational resilience is key. But expanding the board by hiring non-executives with technology expertise might give a false sense of security. As Stilpon Nestor concludes: “There is no single best practice, the model needs to be a function of where expertise lies. Ultimately, cybersecurity is a business issue.”

This article has been prepared in collaboration with Aktis and Nestor Advisors, supporters of Board Agenda.

SPONSORED

SPONSORED