“Don’t talk, but clean.” Unilever chief executive Paul Polman likes to quote this apparently well-known Dutch proverb to explain how his company headed off an opportunistic $143bn takeover approach from American groceries giant Kraft Heinz in February.

Maybe there’s something lost in translation. Polman admitted as much after the event, settling on “let’s just deliver” as his battle cry and crediting his “Calvinist Dutch approach” for allowing the company’s actions to do the talking.

It’s not what was expected from a man best-known for his passionate communication of the importance of sustainable development and a sense of purpose in business. Then again, Polman did act with uncommon speed to derail this bid that never was. He is said to have gathered his advisers, made an impassioned speech about the need to defend Unilever, and asked them to confirm their allegiance to him and the company.

He then wrote directly to Kraft Heinz’s two largest shareholders—US investor Warren Buffett and Brazilian private equity firm 3G Capital—to inform them that an offer would not have the support of the Unilever board and that the Anglo-Dutch company would use every tool at its disposal to fend it off.

Kraft Heinz duly announced that it was withdrawing its offer “amicably”—just 48 hours after admitting its interest in the consumer goods manufacturer.

For all the contrasts drawn between the short-term profiteering of 3G’s leader Jorge Lemann, and Polman’s commitment to long-term sustainable outcomes, Unilever’s bid defence still seems to have been wrapped in the complexities of Dutch corporate culture.

Dutch companies are more consensual and less prone to shareholder activism than their Anglo-Saxon cousins, while foreign takeovers in the Netherlands are protected against by “poison pills”, and dual management and supervisory board structures.

This is a powerful combination that also derailed this year’s $29.5bn attempt by US coatings group PPG Industries to buy Dulux paint-maker AkzoNobel.

Calling it quits

Professor John Colley, of Warwick Business School, an expert in international mergers and acquisitions, says: “Unilever and PPG both clearly took the view that they were not only up against intransigent boards … but also Dutch courts and the government. A hostile takeover bid against such opposition was likely to be both expensive and protracted.

“And as the US dollar declined against the euro, the takeovers became more expensive too.”

Kraft Heinz’s official statement on the failed bid agrees with at least the first part of this. “Kraft Heinz’s interest was made public at an extremely early stage,” says company spokesman Michael Mullen.

“Our intention was to proceed on a friendly basis but it was made clear that Unilever did not wish to pursue a transaction. It is best to step away early so both companies can focus on their own independent plans to generate value.”

But what does Unilever’s Dutch defence mean for this Anglo-Dutch business, and will it change the terms of any future takeover attempts of British companies?

Long relationship

Anglo-Dutch business relations have a mixed track record dating back 400 years, to the time when the English and Dutch set up rival East India companies within 15 months of each other.

Then, in 1826, a British foreign minister sent his country’s ambassador in The Hague a coded message stating that: “In matters of commerce the fault of the Dutch is offering too little and asking too much.”

Some 80 years later, Royal Dutch Shell was created. Then came Unilever, born from a 1930 merger of Margarine Unie of the Netherlands with Britain’s Lever Brothers.

Publisher Reed-Elsevier arrived via a merger in 1996, while British Steel and Hoogovens united as Corus in 1999, the same year that Reckitt & Colman combined with Dutch household products group Benckiser to form Reckitt Benckiser.

Only the latter, which swiftly integrated into a single company, has been an unqualified success. The rest had a legacy of joint boards, joint chairmen or, even worse, joint CEOs. Shell finally demerged in 2005. Unilever, for example, still has two parents, Unilever NV and Unilever plc, which operated with two chairmen until 2005.

The companies’ boards are the same and Dutchman Marijn Dekkers now chairs each, with the firms and their subsidiaries operating as near as possible as a single economic entity, while remaining distinct corporations with their own shareholders and stock exchange listings.

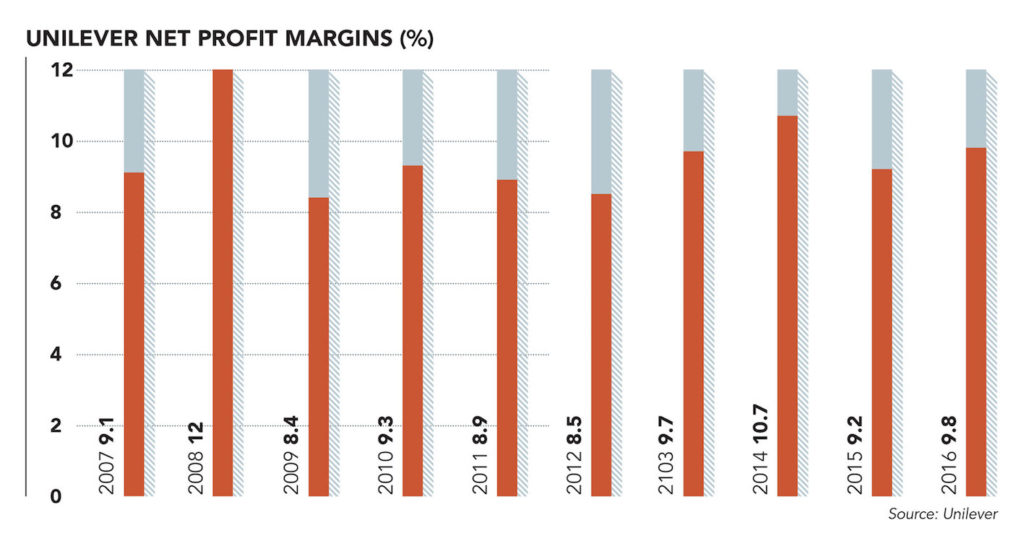

However, while Unilever’s share price underperformed until the bid, most recent grumbles about the group were aimed not at its cumbersome structure, but at the commitment that Polman has made to generating long-term sustainability, rather than pure shareholder value.

One of his early actions was to abandon Unilever’s quarterly reporting of its financial results on the basis that it was too short-termist. He moved the employee share scheme’s goalposts from three to five years for the same reason.

For Polman, the driving force is alignment with customers, with genuine shareholder returns produced when the company understands its consumers intimately and reflects their concerns by operating responsible, purpose-driven brands.

He has put purpose at the heart of Unilever, making public statements on human rights, violence and discrimination against women, sustainable development and infrastructure, and climate change.

Polman claims that the Unilever brands that meet the highest standards for social and environmental impact are growing 40% faster than the group’s other products.

A near-death experience

Before the Kraft Heinz approach, this philosophy was coming under attack, with some shareholders anxious for more growth.

Ironically the bid played into Polman’s hands, with the American company easily caricatured as displaying the opposite kind of capitalism to Unilever’s.

In an open letter to Polman published in March, Richard Buxton, chief executive of Old Mutual Global Investors, called the Kraft Heinz bid a “near-death experience” for the company.

“Unilever is a poster child for the pursuit of long-term, sustainable returns,” he wrote. “3G/Kraft/Heinz is a throwback to the 1980s antics of the late Lords Hanson and White [at Hanson Group].

“Do not succumb to the voices of short-termism. Rally your board, employees and shareholders around your business model and balance sheet. It is not just Unilever at the crossroads: the right or wrong sort of capitalism is at stake.”

Value creation

After Kraft Heinz’s withdrawal, Unilever launched a comprehensive review of “options to accelerate value creation”. This produced plans to offload the margarine spreads business, review its dual Anglo-Dutch structure, increase its dividend and debt levels, launch a €5bn share buy-back, and arrange its continuing business to enable easier separation of its food operations into a standalone company.

Dekkers described the plans as a “balance” between a conservative approach and a capitalist one based on “huge leverage and cost reduction”.

Polman, meanwhile, drew a different balance between not giving up on a long-term sustainability model that has delivered total shareholder return of 190% under his stewardship, and “satisfying increasingly a group of shareholders who want to see at any time the short-term return.”

Wake-up call

Unilever will progress its post-bid plans, plus the “Connected 4 Growth” cost-cutting strategy that the company quietly unveiled in November, promising to make itself more market-facing and agile.

Unilever does seem to accept, however, that the failed bid was a wake-up call—that it could not continue operating in exactly the same way.

“While we rejected their proposal, we do see it as an inflection point,” chief financial officer Graeme Pitkethly told a New York conference the week after the bid intention was withdrawn.

–Paul Polman, Unilever

Saying that he was issuing a “mea culpa” over the group’s communications, he added: “Quite simply, we should have done a better job of landing the message.

“The bid substantially undervalued Unilever but the events show us the challenge to unlock more value faster in the shorter term, rather than focusing more heavily on steady value creation over the longer term, which is what we do.

“This has certainly been a trigger moment for Unilever and we will not waste it.”

As the Financial Times commented in April, however, Unilever’s post-bid plan essentially means that “Unilever is 3G-ing itself half-heartedly”.

“Unilever’s management was unfortunate in that Kraft Heinz was easy to discourage,” warned the paper. “The next bidder may not be.”

Takeover protection

Perhaps that’s why Polman is calling on prime minister Theresa May to review Britain’s takeover protection, learning lessons from Kraft’s Cadbury takeover and Pfizer’s failed bid for AstraZeneca.

“In the UK, although you have it written that the board needs to protect the interests of a broad range of stakeholders, it is very much shareholder-oriented,” he complained. “Some other countries have a broader view.”

No prizes for guessing which nation Polman might be referring to most, and the dual-listing review may come up with a solution, leading Unilever to say goodbye to its London stock market listing and headquarters.

“It would be irresponsible to jump to a conclusion without having done the work,” said Polman in April. “But what we have discovered as we drive to unification [is that] we actually have more possibilities to guarantee the future of this company.”

PAUL POLMAN IN QUOTES

“Refugees are often young and bring diversity and skills. Many have qualities related to perseverance, overcoming challenges, hard work and an ability to problem-solve, as well as self-motivation. Not surprisingly, countries that embrace refugees usually have a healthier outlook.” Unilever press release, 20 June 2017

“Our recent review concluded once more that our strategy for long-term value creation through growth and compounding returns on investment is the right one for Unilever and for our shareholders. It also highlighted the opportunity to go faster and further. The progress already made with Connected 4 Growth allows us to now accelerate the programme.” Unilever press release, 6 April 2017

“Actually, that is one of the key issues in the world right now – the lack of global governance in a world that has become far more interdependent. Some countries have played their role historically, but seem to be falling back to their home base; others have not been able to step up to the plate, claiming developing market status. But increasingly the issues that we are facing – climate change, unemployment, social cohesion, food security – these are issues of global proportions. We are often trapped in short-termism … or other things.” The Guardian, 25 January 2016

“I don’t call it courage. I just call it leadership.” On running Unilever, Forbes, 20 July 2015

Andrew Cave is a business journalist who has written for The Telegraph and Forbes.