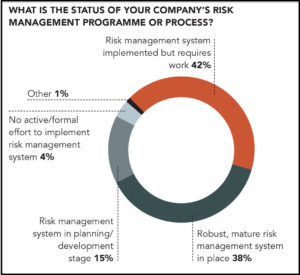

A considerable number of audit committee members believe their organisation’s risk management system requires “substantial work”.

This sobering conclusion comes from KPMG’s Audit Committee Institute, which surveyed more than 800 non-executives from 42 countries across the globe.

The 2017 Global Audit Committee Pulse Survey found that 42% see a requirement for much more effort to be placed upon risk systems and processes. In a world of economic and political uncertainty, technological advances, cyber-threats and market disruption, audit committee members are worried their companies have failed to fully grasp the nettle of both short and long-term priorities.

Warning signs of a lack of focus on risk management for non-executives include: presentations to the board that focus too heavily on historical issues or short-term topics; an infrequency of discussion of emerging risks and opportunities; incentive compensation plans tied strongly to short-term goals and metrics; and a lack of focus on assessing non-financial performance such as product/service quality and customer satisfaction.

Audit committee members in emerging economies are generally more fearful, with half of respondents in India and Turkey calling for more effort on risk management, for example.

KPMG associate partner Tim Copnell says that developed nations, including the UK and US, fare better, at 26% and 36% respectively. However, these are still significant proportions.

Velocity of change

Copnell flags up three key issues that are leading to a gap in risk assurance. Firstly, there is too much focus on financial risks rather than operational and regulatory/compliance risks. “There is a question over whether risk management systems look as wide as they should,” he explains.

Secondly, the “velocity” of risk has increased exponentially. Disruptive market players and reputational problems, for example, can emerge within hours or days rather than in months or years.

Lastly, these problems are exacerbated if boards fail to grasp that the world is fundamentally different to that of ten years ago, or even 12 months ago.

And it is in the construction of these boards that Copnell sees fault lines. “Do people really understand the risks from tech and changing business models?” he asks. “They can be hard to comprehend, particularly for boards that were probably constructed for a different century.”

With the average age of non-executive directors at 60, and 53 for executives, can they comprehend the future and understand the wants and needs of the next generation?

Board diversity therefore should be a critical focus, Copnell believes. “Do they think in the same way as the next generation? If they don’t think that way, do they see the risks coming? The future is going to be very different from the past.”

Agility and proactivity

Paul Moxey, a consultant and visiting professor at London South Bank University, says operational and process-led risks can be managed in a traditional, rules-based method.

Strategic risks require a more systemic approach to make them less likely to occur. “There are all sorts of things going on in the world that could test their resilience,” says Moxey. “So think about business continuity: what are the potential ‘big unknowns’? How might they coalesce? You must plan scenarios.”

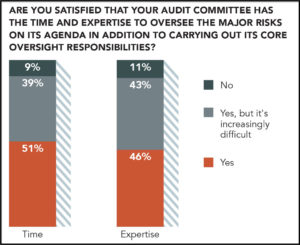

While not all risks can be divined, the ability to act quickly to minimise a threat is a key

aspect of a well-functioning system, and is another area that is causing audit committee member concern, according to Ruth Bender, professor of corporate financial strategy at Cranfield School of Management.

She says that audit committee members must be proactive in “reducing the distance” between themselves and their organisation. “People are conscious that their systems are not agile enough, and can’t react quickly enough to the risks they see, until it is too late,” she explains.

“Even for those that have said they are confident in the organisation’s risk management programmes, what is it that is giving them assurance? They should be benchmarking, visiting its offices, sites, and speaking to staff,” she adds. “It is about demonstrating to the board and its constituents that you will be proactive and find things that should be visible to them.”

Kevin Reed writes on governance and the accountancy sector.