Will greater transparency in high executive pay curb boardroom excess? The high pay packages of top executives have been stirring up widespread concern across continental Europe and the UK, triggering measures to introduce new laws, tighten corporate governance codes and shine a light on opaque remuneration schemes.

In the UK, the government published a corporate governance consultation paper in November 2016, to reform spiralling executive pay. The paper comes as public and institutional investor anger grows over the widening pay gap between elite directors and the rest of the workforce.

The reform proposals have gained strong support from institutional investors, employers’ groups and think-tanks, and followed a joint letter from trade unions, governance professionals and company directors to Theresa May, UK prime minister, earlier this year calling for a clamp down on boardroom excess.

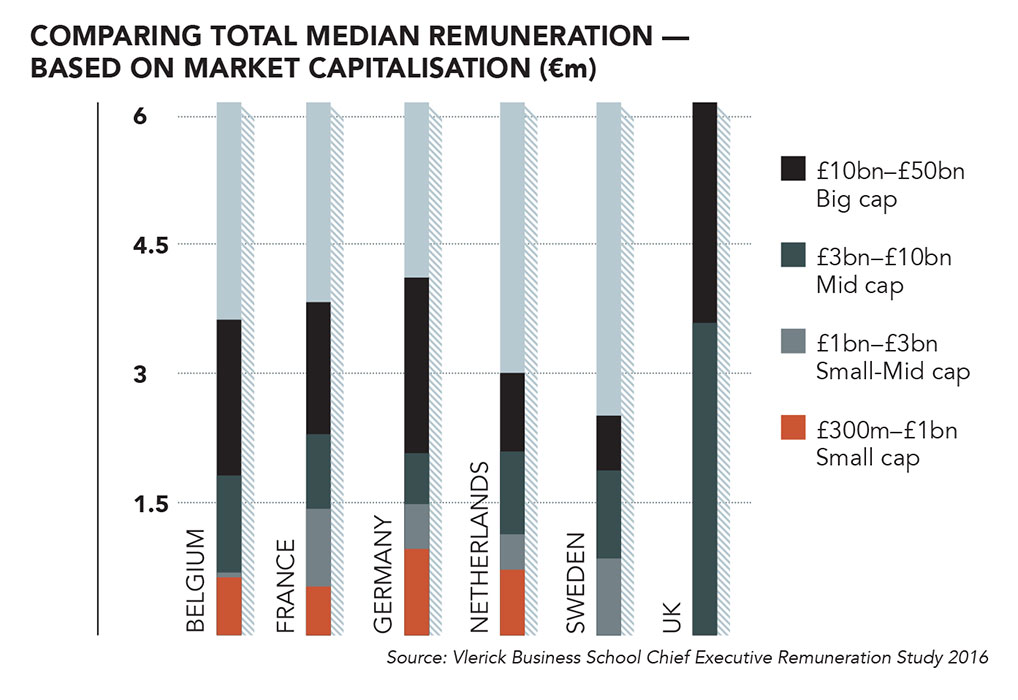

Executive pay levels in UK companies are running particularly high. A study of 701 listed companies, by Vlerick Business School’s Executive Remuneration Centre, showed that UK chief executives were paid much more than their European peers in Germany, Sweden, The Netherlands, Belgium and France in 2015. Among the top-paid UK bosses in 2015 were Sir Martin Sorrell, who received £70m at advertising agency WPP, and Bob Dudley, BP chief executive, with a pay package of £13.3m.

Xavier Baeten, director of Vlerick’s Brussels-based Executive Remuneration Centre, says: “In continental Europe, pay levels of chief executives have not gone up so much as the UK in the past ten years.”

Boosting transparency on executive pay structures is a substantial part of the green paper proposals. They require chief executives to compare and publish their pay with that of the average worker and to boost disclosure over the variable part of remuneration such as bonuses and complex short and long-term incentive plans that push up pay levels. More frequent binding votes on pay by shareholders are also included.

Pay ratios

Stefan Stern, director at think-tank the High Pay Centre, says: “We have pushed hard on publishing pay ratios, which would be an important part of shaping the discussion on pay and bringing more transparency.” He adds that mandatory publishing of pay ratios “is not too much of a stretch for companies to handle”.

Earlier this year BlackRock, the world’s biggest asset manager, took steps to toughen its approach to executive pay excess. In a letter to FTSE 350 chairmen, signed by Amra Balic, managing director of investment stewardship, the asset manager said that “pay should only be increased each year, if at all, at the same level of the wider employee base, and in line with inflation”. BlackRock says companies that make year-on-year pay rises which are out of line with the rest of the workforce must give a clear reason to support the decision.

–Rients Abma, Eumedion

Some European countries have also taken action to strengthen their corporate governance rules. The Netherlands recently revised its code, requiring listed companies to disclose chief executive pay ratios with that of average workers. Companies have to comply with this, or explain in their reporting why they have not done so.

“Retail investors, long-term shareholders and asset managers will take notice of pay ratios,” says Rients Abma, executive director of Eumedion, the Dutch corporate governance and sustainability forum for institutional investors. “When drafting pay policies companies should look at internal pay ratios and benchmarking.”

Abma expects to see increasing pressure from institutional shareholders on companies where the gap between top executives’ pay and the median worker is out of kilter, and more companies being transparent over ratios this year.

The revised Dutch code goes further, requiring chief executives to comment internally on their own pay levels. The comments are then scrutinised by remuneration committees before any top pay schemes are decided.

Making a difference?

But will such measures to boost transparency make a difference to escalating pay levels? Abma believes they do. “We already saw the effects of this. The management board of SBM Offshore [an Amsterdam-listed oil services company] voluntarily proposed a 10% reduction of base pay for a period of 12 months from September 2016, as well as a 50% reduction to any 2016 short-term incentive awards, considering the company’s job cuts,” he says.

Disquiet over high-earning executives in France has triggered new legislation, giving shareholders a binding say on pay and more transparency on the variable part of remuneration packages. Anger came to a head last year when Renault ignored shareholders who voted against the €7.3m pay package of chief executive, Carlos Ghosn, and faced down the anger of the French government, which has a stake in the carmaker.

“We have made everything on pay more transparent: fixed and variable remuneration, benefits, LTIPs,” says Agnès Touraine, chairwoman of the Institut Français des Administrateurs, the association of directors, which supports the new laws.

However, there can be unintended consequences. Touraine points out that an increase of transparency levels over the past ten years resulted in international remuneration comparisons between top executives, triggering pay inflation. “Transparency for the time being has not brought more moderation on pay—it has inflated pay.”

Germany had a similar experience. The government ushered in legislation in 2005, requiring executive remuneration to be published in annual reports, in a push to increase transparency and to decrease executive board salaries.

“The opposite happened as executives looked at other companies’ executive remuneration, and this pushed up pay,” says Manfred Gentz, outgoing chairman of the German Corporate Governance Code Commission. He favours the best-practice pay disclosure approach outlined in the German corporate governance code, where executive “fixed remuneration, bonuses, short-term and long-term incentives, pensions and even a car or subsidised mortgages, as payments in kind, are clearly laid out in two charts, overseen by the supervisory board.”

Gentz hopes that as the supervisory board “sees all these numbers, they will restrict pay increases to a reasonable level, but do so on a voluntary basis.”

Corporate governance review

In the UK, the Financial Reporting Council also aims to beef up governance. The accounting watchdog plans a review of the UK corporate governance code, which would extend its powers to include company directors and pay issues. Companies would have to explain how targets and remuneration are linked to business performance and how they make pay decisions in relation to dividends and capital investment.

Vlerick’s Xavier Baeten says making high pay levels more transparent is likely to help curb excess, but does not believe governments should intervene. “The job of curbing high pay should be done by shareholders,” he says. He believes the key to change “should take place at board level. They should ask ‘is this a decent level of pay?’ You cannot legislate for this.”

–Xavier Baeten, Vlerick Business School

It is not just senior directors who are under scrutiny on pay. The UK government’s proposals for governance reform also raise the question of whether there should be mandatory disclosure on how fund managers vote at annual general meetings. Publishing the rationale for individual voting decisions could throw more light on pay packages.

Stefan Stern agrees that such a reform would be “a helpful move to greater transparency on pay.”

Others do not support mandatory disclosure of shareholder voting. “We think disclosure is good but most institutional investors in the UK do this,” says George Dallas, policy director at International Corporate Governance Network, an investor-led organisation that promotes governance and investor stewardship. He questions how this would work for international investors outside the UK and believes “it would be better to leave it discretionary.”

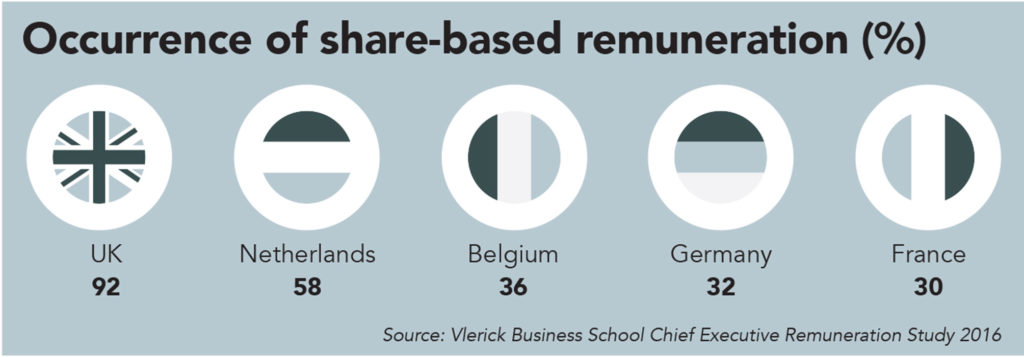

Raising the curtain on executive pay packages in the UK also raises the question of whether such a measure would make it more difficult for UK companies to recruit the best international talent for the top jobs. In 2015, 40% of UK bosses at listed companies were foreign, compared with 31% in Sweden and 28% in the Netherlands and Belgium, according to Vlerick Business School research.

But Stern does not believe this is a problem for the UK. “There is no evidence of flight [over pay disclosure] in the UK or people turning down jobs. I don’t think we should be bluffed about deterrents to do us out of transparency.”

The UK is even less likely to be at a recruitment disadvantage with its European peers at a time when a more level playing field on pay disclosure is underway across European Union member states. The EU recently strengthened its shareholders’ rights directive, giving investors a vote on company pay policy—at least every four years—and increasing transparency on the link between directors’ pay and company performance, providing a bigger picture for the basis of pay deals.

As the annual general meeting season warms up this year, shareholders are in fighting mood over pay excess. At Thomas Cook, the FTSE 250 travel company, one-third of investors voted against the chief executive’s bonus plan, which led to a reduction of the payout in February. Other companies are carefully scanning their remuneration proposals ahead of their AGMs.

In such an environment, widespread measures to improve pay transparency could be the right spur to curb boardroom excess. It will certainly give shareholders more muscle to hold boards of big companies to account for out-of-control compensation.

“Now it is up to the shareholders to vote with their feet if they do not see enough transparency on pay,” says Ms Touraine.