Consultants, business leaders, and activists frequently declare that a strong business case exists for firms to increase the racial/ethnic diversity of their employees. Unfortunately, the reality is that in terms of robust empirical evidence, the jury is still out. Bear with us as we explain.

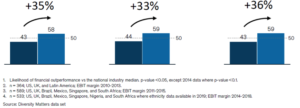

The key piece of evidence put forward in support of the business case comes from McKinsey & Company. In a series of three studies, McKinsey report a statistically significant positive relation between the likelihood of financial outperformance and the racial/ethnic diversity of their executives in global sets of large public firms. Exhibit 7 in McKinsey’s most recent 2020 study summarises their findings:

These numbers are impressive, and because they come from arguably the most prestigious consulting firm in the world, they carry great weight with businesspeople. Indeed, McKinsey do a remarkable job collecting data on diversity and other important topics. Nevertheless, we want to highlight three ways in which McKinsey’s studies do not rigorously support the popularly promoted “business case for diversity”.

Past performance and current diversity

First, the direction of causality between diversity and financial performance is not yet established. The business case argues that greater diversity today leads to better financial performance in the future. But McKinsey’s results do not speak to this direction—they speak to the opposite direction. In each of their studies, McKinsey correlate past financial performance (for example, 2010-2013) with at-the-time current executive diversity (for example, 2014). Taken at face value, McKinsey’s results therefore say that better financial performance causes higher executive diversity, not that higher executive diversity causes better financial performance.

While McKinsey quietly acknowledge this in their studies, their public interpretations of their results seem to set aside this crucial problem. For example, Dame Vivian Hunt, McKinsey’s managing partner in the UK and Ireland and a co-author on all three of McKinsey’s studies, states that:

“What our data shows is that companies that have more diverse leadership teams are more successful. And so the leading companies in our datasets are pursuing diversity because it’s a business imperative and driving real business results.”

Second, separate from the causality problem, the correlations McKinsey reports do not appear to survive independent stress tests. In a recent research study, we applied McKinsey’s methods to the firms in the S&P 500 Index as of 31 December 2021.

In contrast to McKinsey, we found statistically insignificant relations between McKinsey’s measures of S&P 500 firms’ executive racial/ethnic diversity as of mid-2020 and their 2015–2019 industry-adjusted EBIT margins. More broadly, we also found statistically insignificant relations between executive racial/ethnic diversity and industry-adjusted sales growth, gross margin, return on assets, return on equity, and total shareholder return.

Third, the inverse normalised Herfindahl-Hirschman or INHH measure of executive racial/ethnic diversity McKinsey use has certain features that call into question its validity.

For example, the INHH measure implies that executive diversity is greatest when a firm has equal numbers of executives from each race/ethnicity. This is problematic because the US population does not contain equal numbers of each race/ethnicity, making it impossible for all firms to maximise their executive diversity.

The INHH measure also counter-intuitively gives the same diversity score to firm A with executives who are representative of the US population (in 2019 approximately 1.0% American Indian/Alaska Native, 6.4% Asian/Pacific Islander, 13.0% Black, 18.5% Hispanic, 61.1% White) as to firm B with executives who are the very opposite of representative of the US population (for example, 61.1% American Indian/Alaska Native, 18.5% Asian/Pacific Islander, 13.0% Black, 6.4% Hispanic and 1.0% White).

Careful attention—and caution—needed

Where then does our research as compared to McKinsey’s studies leave the debate with regard to executive race/ethnicity and firms’ financial performance? We’d like to suggest four takeaways.

One: Whether done by academics or practitioners, there is likely great value to be gained from future research that seeks to empirically identify and measure the directions and magnitudes of the causal relations between racial/ethnic diversity and firm financial performance. And not only for large firms such as those in the S&P 500, but across a wide variety of companies, both in US and international. This would bring into sharper focus the benefits/returns and costs/risks of racial/ethnic diversity, not only with regard to firms’ executives, but their boards of directors, rank-and-file employees, and other key stakeholders.

Two: There’s also likely high value in work that emphasises stress tests. Whether done by businesspeople or academics, studies that seek to replicate high-profile findings such as McKinsey’s warrant encouragement and dissemination. Columbia Business School professor Shiva Rajgopal recently urged this in Forbes, and we heartily agree with him.

Three: How diversity is defined and measured deserves more careful attention. While we commend McKinsey for being explicit about how they define and measure executive racial/ethnic diversity, diversity metrics should include the calibration of observed racial/ethnic proportions against one or more benchmarks. And as we find in a different research study, the choice of racial/ethnic benchmark can matter a great deal, especially when evaluating under- versus overrepresentation.

Lastly: We recommend that businesses view consulting and advisory firm reports with caution as well as respect. Businesspeople instinctively understand that caveat emptor applies when it comes to making money. Not as well appreciated is that caveat emptor also applies to the results and conclusions in high-profile research reports—including those written by academics such as us. Keeping an open mind, especially in important and sensitive areas such as race/ethnicity is, we believe, an important and worthwhile posture for businesspeople to take.

John R. M. Hand is the Robert March & Mildred Borden Hanes distinguished professor of accounting at UNC’s Kenan-Flagler Business School.

Jeremiah Green is an associate professor of accounting at the Mays Business School at Texas A&M University.