‘The government needs to push through key business reforms’

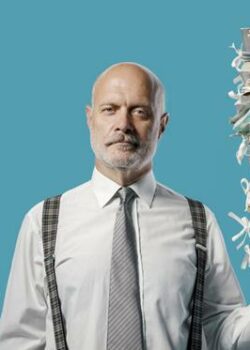

Roger Barker, head of corporate governance at the Institute of Directors

The UK General Election delivered an overwhelming political mandate for the Conservative government. As well as using this mandate to break through the Brexit logjam, I hope that some of the accumulated political capital will be used to undertake other important business policy reforms which—for the last year or so—have been largely neglected due to a lack of government priority or legislative bandwidth.

Of particular concern is the uncertain future of some key reforms relating to the UK’s internationally respected corporate governance regime.

For example, although the Financial Reporting Council has already taken some tentative steps towards transforming itself into a more robust audit regulator—the Audit, Reporting and Governance Authority—primary legislation is needed in order to take this process forward. Such legislation needs to be introduced into Parliament as soon as possible.

Ambitious reforms have also been mooted by the government for the UK’s Company Register at Companies House. The proposed changes would radically improve the accuracy and integrity of information held about companies, their directors and those exerting significant influence or control. However, once again, it remains uncertain as to when the necessary legislation will actually see the light of day.

A third example is particularly topical. At the beginning of 2019, an independent airline insolvency review proposed reforms which could have prevented much of the passenger chaos observed during the collapse of Thomas Cook. However, whether due to the distraction of Brexit or for other reasons, the common-sense suggestion of a new special administration regime for airlines has not yet made it onto the statute book.

Of the three main political parties, the Conservative election manifesto had the least to say on matters relating to corporate governance. It is hoped that this silence does not reflect an indifference regarding the importance of our corporate governance framework. Ultimately, if the UK’s corporate governance regime is to remain the jewel in the crown of our post-Brexit economy, the new government must discover the will and the parliamentary time to push through these important business reforms.

‘Authentic, empowered challenges from the shopfloor’

Luke Hildyard, executive director at the High Pay Centre

Mandatory publication of company pay ratios will begin in 2020, together with reports of how directors have fulfilled their legal responsibilities to stakeholders beyond their shareholders. The new corporate governance code is also now in force, and states that the UK’s leading listed businesses should take steps to include a broader range of stakeholder voices at board level. Options recommended are a) an elected workers’ representative b) a formal committee comprising identified stakeholders or c) a non-executive director with designated responsibility for stakeholder-related issues.

My hope for 2020 is that businesses engage seriously with the spirit of these new requirements.

Firstly, they should reflect on the reputational impact of their pay ratio; think about how very high pay for their highest paid employees affects on what they can afford for low and middle earners; and properly interrogate whether vast pay packages are proportionate or necessary to business success.

Secondly, the new disclosures on directors’ stakeholder responsibilities should show clear, sincere plans—underpinned by data and forward-looking targets—for providing more fulfilling, better-paid, progressive careers within their organisations. They should also articulate a credible analysis of the wider social and economic value of the company’s work and their contribution, for better or worse, to meeting the pressing environmental challenges facing the world today.

Boards are under immense pressure to deliver emphatic returns to shareholders at all times. Our research found that buybacks and dividends increased by 56% from 2014-2018, 6 times faster than wages for the average UK worker. 22% of dividend income in the UK goes to approximately the richest 1% of the population—evidence that business has a purpose beyond helping the rich get richer is needed.

Finally, I hope that a significant number of companies will opt for the worker director or stakeholder committee options for stakeholder voice in corporate governance structures, rather than unanimously picking the least disruptive choice, a NED with responsibility for stakeholder affairs.

Authentic, empowered challenges from the shopfloor—or from NGOs or consumer groups—will help align business actions with the interests of wider society. It cannot thrive in the 2020s unless this is the case.

‘It’s time for directors to drop compliance preoccupation’

Andrew Kakabadse, professor of governance and leadership at Henley Business School

Many boards shout loudly about their sustainability efforts and the subject is high on the agenda of numerous organisations which have adopted and champion the rhetoric of triple bottom line reporting.

Sadly, this public visibility often masks a reality where sustainability is a low priority initiative, often viewed as an imprecise concept attracting ecological interest, but which does little to minimise genuine environmental harm in a world of rapidly depleting natural resources.

While 2019 will perhaps be looked back on as the year of #Activism, with social media inspiring real action through #ClimateStrike, #PeopleVote, #MeToo and #TimesUp to name a few, social pressure on business and governments to become ever more ecologically and socially responsible will increase throughout 2020. Environmental disasters, social injustice, enlightened investors and citizens, as well as changing public expectations will push sustainability to the top of the director’s agenda.

These pressures should incentivise governments and local political bodies to introduce new and appropriate legislation. By way of example, Bristol City Council has already proposed a ban on all diesel vehicles within its city centre, and will raise a congestion charge from 2021.

Legislation and social pressures are likely to force boards to make significant environmental disclosures, including data on greenhouse gas emissions, water usage, waste disposal, labour relations, product and service safety, employee wellbeing and progress in diversity.

This, of course, comes in addition to the board’s already hectic fiduciary duty to oversee company strategy, risk, data protection, cybersecurity and shareholder and stakeholder rights.

From 2020 onwards boards will feel palpable demand from investors and other stakeholders to proactively evaluate competitive threats and better understand disruptive market trends. Similarly, directors will be required to engage effectively across emerging organisational misalignments, integrating sustainability and corporate purpose with financial short-termism.

All of this is set against a need to continue achieving distinct competitive advantage. Linking sustainability to business strategy requires enhanced disclosure mechanisms to promote the firm’s reputation and achieve active engagement with multiple stakeholders.

None of this will be possible if directors continue to remain needlessly preoccupied with compliance.

The oversight function of boards is about balancing compliance against stewardship. This requires directors to facilitate difficult conversations, using monitoring and mentoring to help integrate sustainability with financial challenges.

2020 is set to test the resolve of directors’ ability to adapt their enterprises to be sustainability prepared. Boards need to rethink their role and contribution towards actively caring and being seen to do so, while placing controls around certain activities that will fully stretch their intellectual capacity and resilience.

‘Tremendous opportunities for leadership, innovation and collaboration’

John Morrison, chief executive of the Institute for Human Rights and Business

Every year on human rights day, 10 December, the Institute for Human Rights and Business (IHRB) publishes its list of the top ten issues that should be on businesses’ agendas for the coming year. The list for 2020 does not pull its punches, and the list of challenges are hard hitting:

• Just transitions Confronting the climate crisis while fostering rights-respecting jobs and empowered communities

• Fake news Harnessing collective power to combat lies and propaganda online

• Purpose Redefining the role of corporations to align with societal expectations

• Cities Embedding dignity while building communities

• State action Expanding calls for mandatory human rights due diligence

• Sexual harrassment Transforming cultures and developing robust grievance mechanisms to eliminate abuse at work

• Weaponising lawsuits Stopping the practice of blocking human rights defenders from challenging business activity

• Surveillance Establishing safeguards for new technologies that may undermine rights

• Worker voice Defending rights of assembly and speech at work

• Gender identity Understanding gender fluidity and making workplaces inclusive.

This is in large part due to the context surrounding us all as we enter a new decade: that multilateralism itself and many of our international institutions are under attack, the climate crisis is at the point of no return, and the future of work itself is in a profound state of change.

But what might mark the biggest difference between the start of this decade and the last is the evolution of the dynamics between business, civil society, and governments when it comes to human rights and social impact. Over the last ten years or so, we have seen each group move from a general state of mistrust and antagonism to an emerging reality of engagement and endeavours toward collective problem-solving.

This should offer some relief to those working to balance the financial needs of a company with the non-financial, because there are tremendous opportunities in each of the above areas for corporate leadership, innovation and collaboration. Our biggest hope for 2020 is that more businesses seize the opportunity, beyond the largest consumer-facing brands that have blazed the trail so far.

‘Significant changes to the work of the audit committee’

Peter Swabey, policy and research director at the Chartered Governance Institute

2020 is shaping up to be a busy year in many ways and, although governance may not be at the top of the agenda for the new government, there will be plenty to keep us occupied.

Commitments in the Queen’s speech include support for flexible working and childcare, which will begin to address some of the socioeconomic issues underlying the problem of diversity in the boardroom and the boardroom pipeline, as well as the gender pay gap. The government has also undertaken to build on the CMA, Kingman and now Brydon reviews of aspects of the audit market to create “a stronger regulator with all the powers necessary to reform the sector”.

Sir Donald Brydon’s review of the quality and effectiveness of audit was published recently, all 135 pages of it, with 65 recommendations. Taken together with the CMA and Kingman reviews, these recommendations presage significant changes to a number of aspects of the work of the audit committee and of the company secretary or governance professional who supports it.

Although in many cases they are applicable only to the FTSE 350, it is likely that many of the proposals will be adopted more widely across the market and across sectors. It is good to see some of the issues that the Institute has argued are essential to improve the quality of audit—notably a clear definition of what the audit is for and training to encourage scepticism amongst auditors—picked up in Sir Donald’s recommendations and we await the promised consultations bringing these proposals together with interest.

In the charity sector, the Charity Governance code steering group is consulting on a “light refresh” to the code last published in summer 2017. The consultation is open until 28 February 2020 and it will be interesting to see the feedback received.

Finally, the Chartered Governance Institute will be reporting to the new government on the review commissioned last year to identify further ways of improving the quality and effectiveness of board evaluations, including the development of a code of practice for external board evaluations.