The previous “light-touch” model of bank regulation that preceded and created the conditions for the global financial crisis has been replaced by a far stricter supervisory regime, following the introduction of a welter of new regulations—both across the European Union and on a local level—as well as greater scrutiny from shareholders angered by the destruction of value that ensued.

As a result, banks are now safer from a capital perspective and its executives are more accountable than ever before. Change has been rapid, startling and undeniable. Bank boards are now smaller, work harder and more efficiently and have a higher level of expertise than a decade ago, while gender diversity has improved.

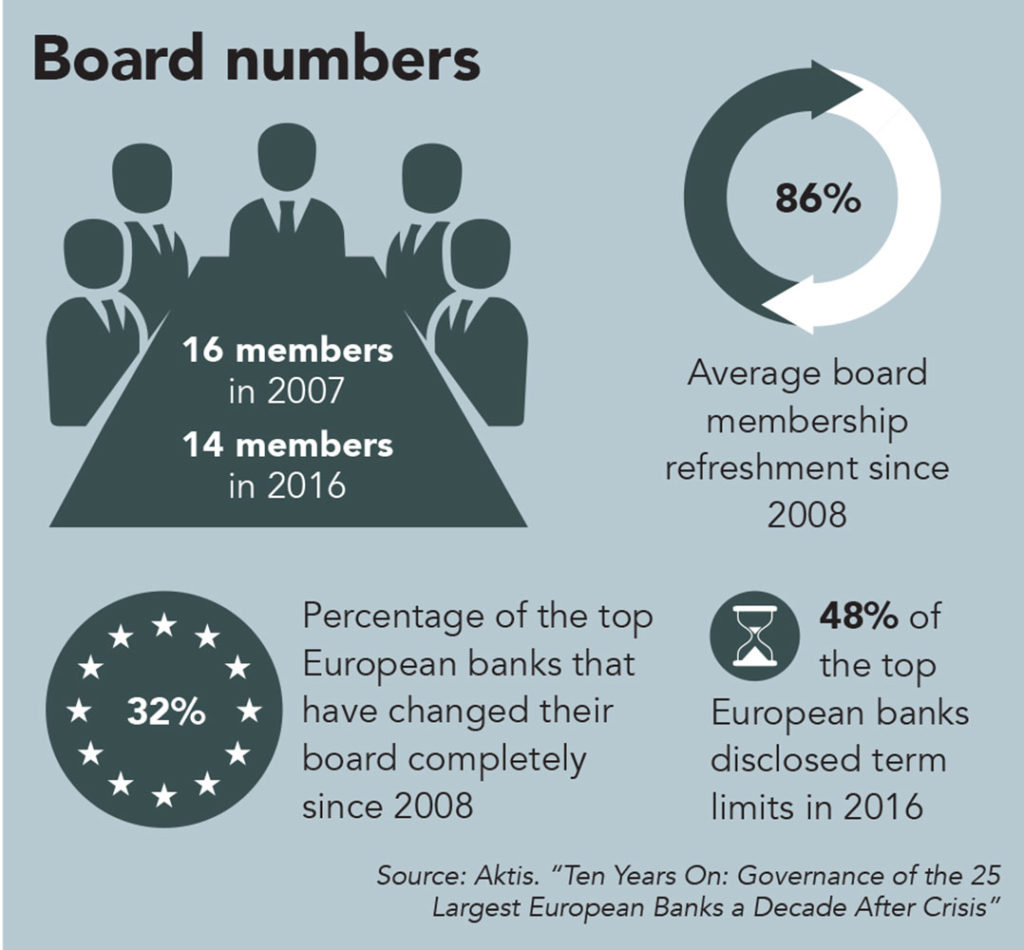

Fresh leadership has emerged on a tide of greater accountability. In the past decade, on average 86% of board membership has been refreshed at Europe’s top banks, according to Aktis, a global consultancy which provides bank governance data.

The Aktis data, which draws on an extensive analysis of corporate governance at the biggest 25 banks in Europe by market capitalisation since the financial crisis, shows that in total 32% of top European banks have changed their board completely since 2008.

“Previously bank governance was a black box for regulators and supervisors,” says Stilpon Nestor, founder and CEO of governance advisory firm Nestor Advisors. “In the previous era of light-touch regulation there was an assumption from the regulator that it was the business of the firm to do what it liked when it came to governance. The change from that position has been significant and most welcome.”

While some banks are still trying to find the right business model, governance has been transformed both through a raft of new regulations and increased supervision as the introduction of legislation such as the Capital Requirements Directive IV (CRD IV) on a Europe-wide level, as well as local initiatives, have transformed the governance landscape for the better.

“Supervisors have also developed quite detailed expectations as to what they want to see from governance, and in their supervisory on-sites they are more focused than ever on governance issues,” says Nestor.

Banks are more robust with stronger capital buffers, and executives are more accountable, with new rules on compensation providing boards with the power to claw back bonuses where they see evidence of misconduct. Some local supervisors have gone even further, such as in the UK, where the introduction of the Senior Managers Regime by the Financial Conduct Authority has made top executives accountable and personally liable for strategic and operational shortcomings. Monitoring is stronger than ever.

As a condition of CRD IV, all top European banks must conduct regular assessments of the effectiveness, composition and functioning of the board and just under half disclose that they retain an external adviser to facilitate this evaluation. Aktis has a key role to play in this dialogue.

Checks and balances

The central role of the board is to provide checks and balances on senior management and to ensure the company is working in the long-term interests of its shareholders. Regulation has ironed out the inherent weaknesses that previously existed on the boards of big banks.

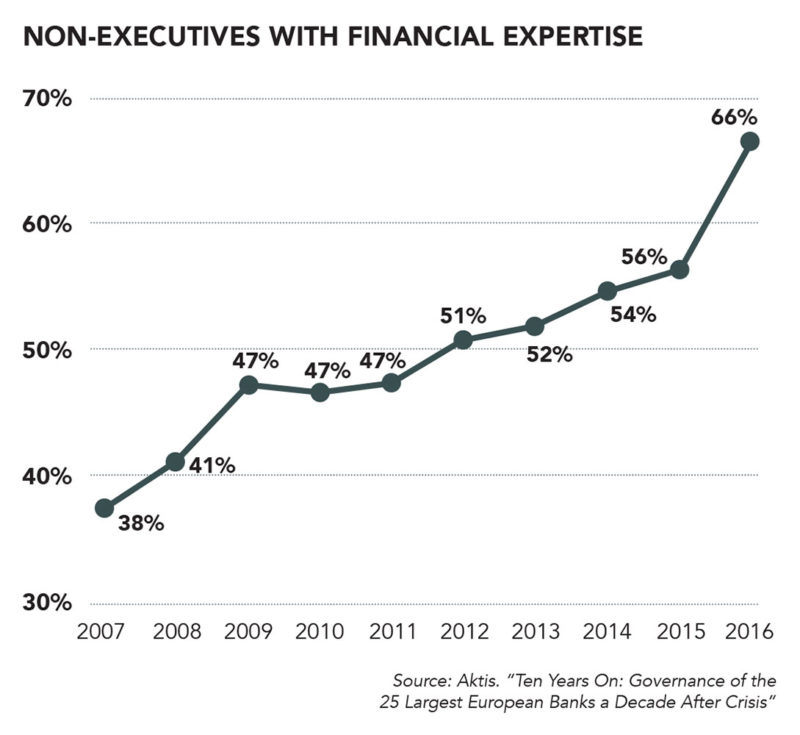

In the run-up to the crisis, bank boards became dominated by individuals with little or no financial experience, and therefore little understanding of the increasingly complex financial instruments that exacerbated the global contagion which, in turn, accelerated the crisis.

The Aktis report shows that each of the top 25 European banks now have at least one non-executive director on the board with recent senior management experience in the financial industry, and 44% now include at least one non-executive on the board who has held a senior risk management position.

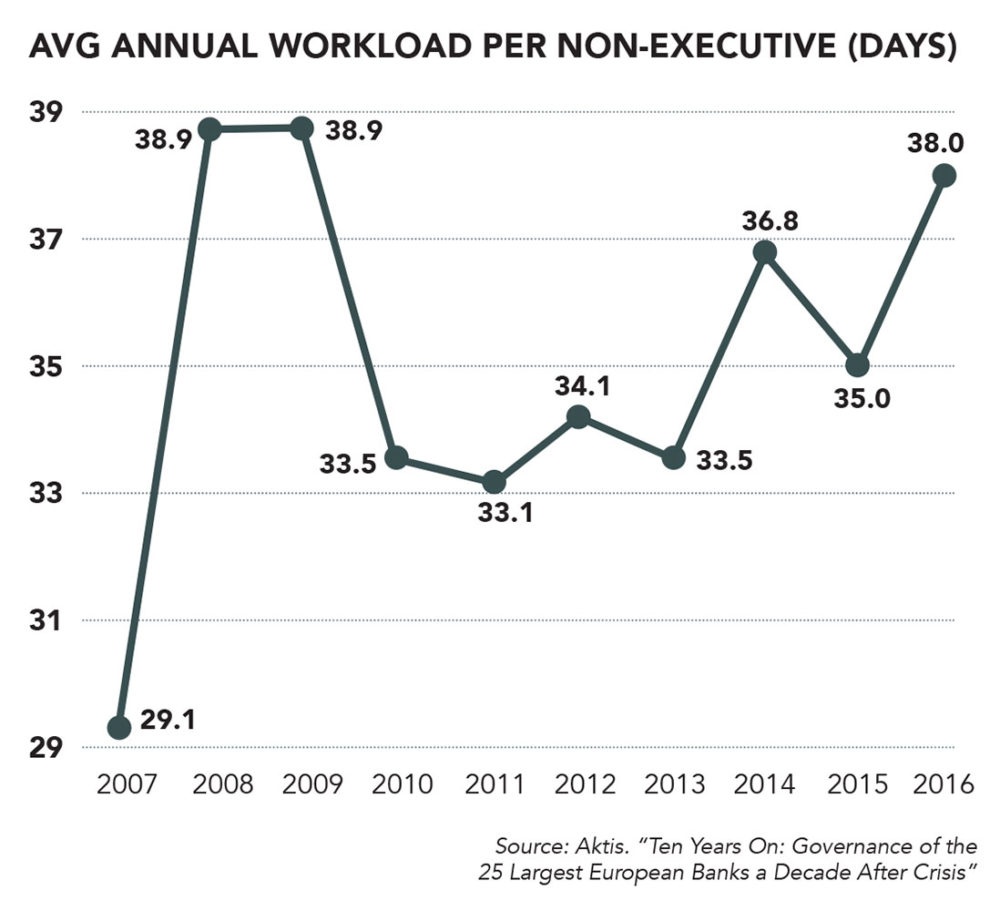

The influx of new board members has brought greater independence and have been specifically selected where they have relevant industry experience, while there is also an improved gender balance at board level. The role of non-executive directors has also evolved, with boards of financial institutions demanding a greater time commitment. On average, the workload per director has increased by a third compared with pre-crisis levels, and pay has doubled, Aktis says.

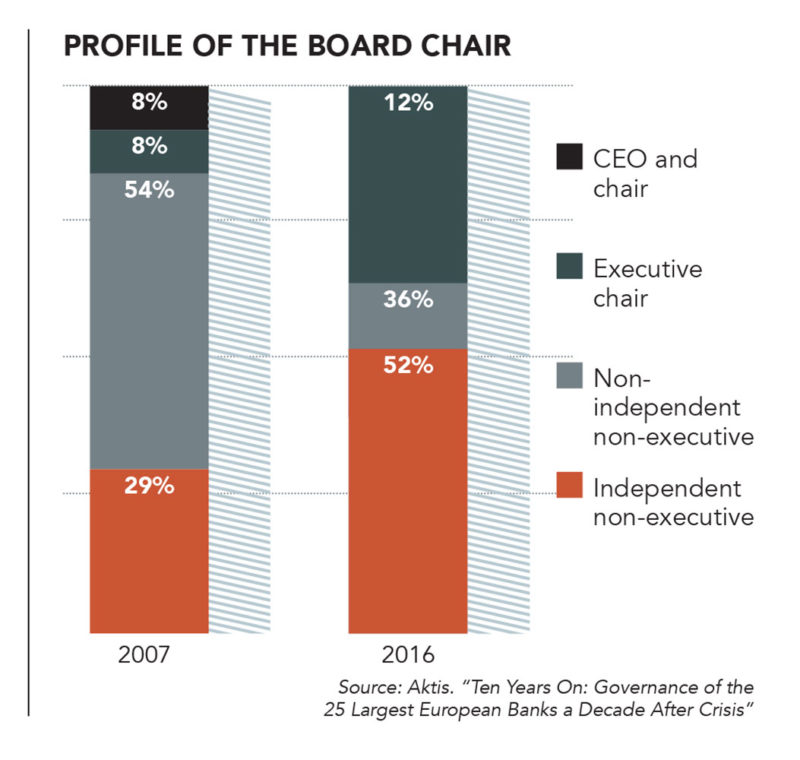

The proliferation of more non-executives on bank boards is the result of shareholder pressure, while regulators have also moved to stamp out some of the worst excess. The introduction of CRD IV in 2014 heralded the end of the joint CEO/chairman role at European banks. This had grown out of the role of the old-style executive chairman, who gradually took on more and more responsibility before becoming an all-conquering force that was difficult to control.

The eradication of that role means that the profile of the chair of the board has undergone a radical shift, with 80% of banks having appointed a new chairman since 2008. Fifty-two percent of chairmen are now independent non-executives, compared with 29% a decade ago, according to Aktis. At the same time, the splitting of the role means that new-style bank chair people are taking on more executive responsibility amid greater levels of delegation from the CEO.

Risk management sits at the centre of banking and it is no coincidence that those firms which escaped the crisis relatively unscathed were those with a strong risk culture. Conversely, those banks that were bailed out by taxpayers either had inadequate risk management or neutered the function as it was regarded as an unhelpful brake on runaway growth, rather than an essential means of preserving shareholder value.

Banks have strengthened their risk function, and the chief risk officer is now a member of the management committee of all banks, compared with only 55% in 2007. Heads of compliance and legal functions are increasingly members of management committees, as the Aktis data shows.

Board sizes have shrunk, enabling greater control and more debate. Smaller boards are generally considered to be more effective and cohesive while they have segmented their work into more specialist committees.

Indeed, the number of committees supporting the board has grown consistently since 2008, driven in part by the mandatory separation of the audit and risk committee into two distinct entities. The increased focus on the role of the board has prompted a growing number of banks to establish more and more committees focusing on regulatory and compliance matters, as well as culture, conduct and reputation as they emerge from numerous crisis-era scandals that have cost the industry billions of dollars in fines.

Force for good

The significant progress in governance and supervision has undoubtedly been a force for good, but the seemingly constant tide of new regulation has also given rise to unintended consequences and there are fears that excessive regulation and the shifting structure of boards risks undermining banks’ systems of governance.

“We should be now entering an era where we take stock of what has been done and possibly adjust it, not with more but with less,” says Nestor. “While it’s right to say it’s been a force for good overall, it is not 100% good. For example, there is micromanagement from the supervisor in certain cases.”

In some cases, the guidance has become too rigid, such as the requirement from the European Banking Authority preventing the chairperson of the board from occupying a similar position on the governance committee. This could undermine the ability of the board to hold management to account, replicating the situation pre-crisis where management committees enjoyed unrivalled power.

“There is a misconception that you have to distribute power and create a structure where every committee competes and challenges one another,” explains Nestor. “That’s not how boards work. Boards are there to challenge management, and to do that there needs to be somewhere on the board where there is power—and that should rest with the chairperson.”

The rise of the non-executive

The rise in the number of non-executive directors to challenge senior management and take a view on strategy is welcome, but in some cases, this has been accompanied by a reduction in the number of executives who sit on bank boards.

“A bank’s executives are the people who run the bank and are directly accountable to the shareholders and members of the board,” explains Nestor. “The more executives who sit on a board, the more other members can gain a clear picture of the bench strength of the executive team.”

At the same time, having too many non-executives means that decision-making power is concentrated in the hands of people who are not full-time employees of the bank and are not present at the coal-face, and therefore not aware of the many challenges a bank faces daily.

The raft of new regulation was designed to solve the last crisis and fix the mistakes of the past, but there is a danger that this could mean the seeds of the next crisis are overlooked.

The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision is looking to implement the next phase of regulatory reform—known as Basel IV—which, among other things, could result in the imposition of standardised measures for operational risk.

“The evolution of regulation means banks have moved from ‘light-touch’ to the other end of the spectrum, where they can no longer build their own machines when it comes to risk,” says Nestor. “It’s important to have a common denominator of transparency, but banks should have the ability to use internal models to mitigate and understand risk.”

Bank governance has been transformed over the past decade, leading to more rigour and boards that work harder, have more expertise and are more diverse. But banks should now assess how far they have come and monitor whether they have the right composition of talent on their boards, to ensure they are best-placed to deal with the next crisis when it comes.

Ten years on: Bank governance in numbers

Key findings from Aktis:

• The average board size has shrunk to 14 from 16 in 2007

• 80% of banks have appointed a new chair since 2008

• 34% of women are on bank boards, up from 15% in 2007

• 66% of NEDs have financial expertise, compared with 38% a decade ago

• Total remuneration for NEDs has increased by 60% but so has time commitment

• 86% of banks disclose that the board has set a process to review culture and risk culture

• 70% of banks have joint meetings between audit and risk committees, up from 35% in 2007

This article has been prepared in collaboration with Aktis, a supporter of Board Agenda.

SPONSORED

SPONSORED